Five of nine. Continuing the current series of posts, this post looks at the AB Calculus 2021 exam question AB 5. The series considers each question with the aim of showing ways to use the question in with your class as is, or by adapting and expanding it. Like most of the AP Exam questions there is a lot more you can ask from the stem and a lot of other calculus you can discuss.

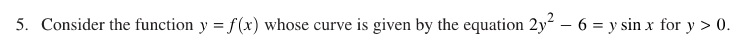

2021 AB 5

This question tests the process of differentiating an implicit function. In my scheme of type posts, it is in the Other Problems (Type 7) category; this type includes the topics of implicit functions, related rate problems, families of functions and a few others. This topic is in Unit 3 of the current Course and Exam Description. Every few exams one of these appears on the exams, but not often enough to be made into its own type.

The question does not lend itself to changes that emphasize the same concepts. Some of the suggestions below are for exploration beyond what is likely to be tested on the AP Exams.

Here is the stem, only one line long:

Part (a): Students were given dy/dx and asked to verify that the expression is correct. This is done so that a student who makes a mistake (or cannot find the derivative at all) will not be shut out of the rest of the question by not having the correct first derivative.

While not required for the exam, you could use a grapher in implicit mode to graph the relation. Without the y > 0 restriction the graph consists of two seemingly parallel graphs similar to a sine graph. They are not sine graphs.

Ideas for exploring this question:

- Using a graphing utility that allows you to use sliders. Replace the -6 by a variable that will allow you to see all the members of this family using a slider.

- If the slider value is between -1/8 and 0 the graph no longer looks the same. Explore with this.

- If the slider value is < -1/8 there is no graph. Why?

- Explain why these are not sine graphs. (Hint: Use the quadratic formula to solve for y):

.

Part (a): There is not much you can change in this part. Ask for the derivative of a different implicit relation. You may use other questions of this type. Good Question 17, 2004 AB 4, 2016 BC 4 (parts a, b, and c are suitable for AB).

Discussion and ideas for adapting this question:

- Ask for the first derivative without showing student the answer.

- Find the derivative from the expression when first solved for y. Show that this is equal to the given derivative.

Part (b): An easy, but important question: write the equation of the tangent line at a given point. Writing the equation of a line shows up somewhere on the exam every year. As always, use the point-slope form.

Discussion and ideas for adapting this question:

- Use a different point.

Part (c): Students were asked to find the point in a specific interval where the tangent line is horizontal.

Discussion and ideas for adapting this question:

- By enlarging the domain find other points where the tangent line is horizontal. (Not likely to be asked on the exam, but good exercise.)

- Using y < 0 find where the tangent line is horizontal. (Not likely to be asked on the exam, but good exercise.)

- Determine if the two parts of the graph are “parallel.”

- Determine if the two parts of the graph are congruent to

.

Part (d): Students were asked to determine if the point found in the previous part was a relative maximum, minimum or neither, and to justify their answer.

Discussion and ideas for adapting this question:

- Have students justify using the Candidates’ test (closed interval test).

- Have students justify using the first derivative test.

- Have students justify using the second derivative test.

- Ask the same question for the branch with y < 0.

Having students justify local extreme values by all three methods is good practice any time there is a justification required. Depending on the problem, it may not be possible to use all three. Discuss why; discuss how to decide which is the most efficient for each problem.

Next week 2021 AB 6.

I would be happy to hear your ideas for other ways to use this question. Please use the reply box below to share your ideas.