Unit 5 covers the application of derivatives to the analysis of functions and graphs. Reasoning and justification of results are also important themes in this unit. (CED – 2019 p. 92 – 107). These topics account for about 15 – 18% of questions on the AB exam and 8 – 11% of the BC questions.

You may want to consider teaching Unit 4 after Unit 5. Notes on Unit 4 are here.

Reasoning and writing justification of results are mentioned and stressed in the introduction to the topic (p. 93) and for most of the individual topics. See Learning Objective FUN-A.4 “Justify conclusions about the behavior of a function based on the behavior of its derivatives,” and likewise in FUN-1.C for the Extreme value theorem, and FUN-4.E for implicitly defined functions. Be sure to include writing justifications as you go through this topic. Use past free-response questions as exercises and also as guide as to what constitutes a good justification. Links in the margins of the CED are also helpful and give hints on writing justifications and what is required to earn credit. See the presentation Writing on the AP Calculus Exams and its handout

Topics 5.1

Topic 5.1 Using the Mean Value Theorem While not specifically named in the CED, Rolle’s Theorem is a lemma for the Mean Value Theorem (MVT). The MVT states that for a function that is continuous on the closed interval and differentiable over the corresponding open interval, there is at least one place in the open interval where the average rate of change equals the instantaneous rate of change (derivative). This is a very important existence theorem that is used to prove other important ideas in calculus. Students often confuse the average rate of change, the mean value, and the average value of a function – See What’s a Mean Old Average Anyway?

Topics 5.2 – 5.9

Topic 5.2 Extreme Value Theorem, Global Verses Local Extrema, and Critical Points An existence theorem for continuous functions on closed intervals

Topic 5.3 Determining Intervals on Which a Function is Increasing or Decreasing Using the first derivative to determine where a function is increasing and decreasing.

Topic 5.4 Using the First Derivative Test to Determine Relative (Local) Extrema Using the first derivative to determine local extreme values of a function

Topic 5.5 Using the Candidates’ Test to Determine Absolute (Global) Extrema The Candidates’ test can be used to find all extreme values of a function on a closed interval

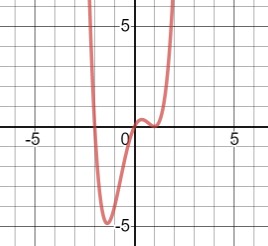

Topic 5.6 Determining Concavity of Functions on Their Domains FUN-4.A.4 defines (at least for AP Calculus) When a function is concave up and down based on the behavior of the first derivative. (Some textbooks may use different equivalent definitions.) Points of inflection are also included under this topic.

Topic 5.7 Using the Second Derivative Test to Determine Extrema Using the Second Derivative Test to determine if a critical point is a maximum or minimum point. If a continuous function has only one critical point on an interval then it is the absolute (global) maximum or minimum for the function on that interval.

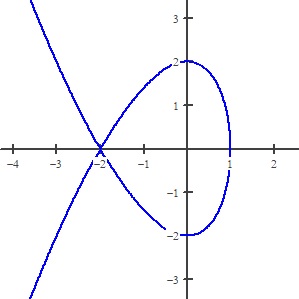

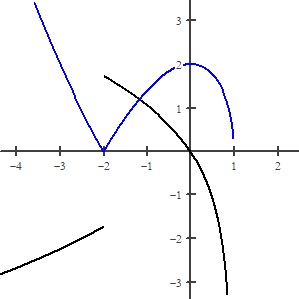

Topic 5.8 Sketching Graphs of Functions and Their Derivatives First and second derivatives give graphical and numerical information about a function and can be used to locate important points on the graph of the function.

Topic 5.9 Connecting a Function, Its First Derivative, and Its Second Derivative First and second derivatives give graphical and numerical information about a function and can be used to locate important points on the graph of the function.

Topics 5.10 – 5.11

Optimization is important application of derivatives. Optimization problems as presented in most text books, begin with writing the model or equation that describes the situation to be optimized. This proves difficult for students, and is not “calculus” per se. Therefore, writing the equation has not be asked on AP exams in recent years (since 1983). Questions give the expression to be optimized and students do the “calculus” to find the maximum or minimum values. To save time, my suggestion is to not spend too much time writing the equations; rather concentrate on finding the extreme values.

Topic 5.10 Introduction to Optimization Problems

Topic 5.11 Solving Optimization Problems

Topics 5.12

Topic 5.12 Exploring Behaviors of Implicit Relations Critical points of implicitly defined relations can be found using the technique of implicit differentiation. This is an AB and BC topic. For BC students the techniques are applied later to parametric and vector functions.

Timing

Topic 5.1 is important and may take more than one day. Topics 5.2 – 5.9 flow together and for graphing they are used together; after presenting topics 5.2 – 5.7 spend the time in topics 5.8 and 5.9 spiraling and connecting the previous topics. Topics 5.10 and 5.11 – see note above and spend minimum time here. Topic 5.12 may take 2 days.

The suggested time for Unit 5 is 15 – 16 classes for AB and 10 – 11 for BC of 40 – 50-minute class periods, this includes time for testing etc.

Finally, were I still teaching, I would teach this unit before Unit 4. The linear motion topic (in Unit 4) are a special case of the graphing ideas in Unit 5, so it seems reasonable to teach this unit first. See Motion Problems: Same thing, Different Context

This is a re-post and update of the third in a series of posts from last year. It contains links to posts on this blog about the differentiation of composite, implicit, and inverse functions for your reference in planning. Other updated post on the 2019 CED will come throughout the year, hopefully, a few weeks before you get to the topic.

Previous posts on these topics include:

Then There Is This – Existence Theorems

What’s a Mean Old Average Anyway

Did He, or Didn’t He? History: how to find extreme values without calculus

Mean Value Theorem

Graphing

Reading the Derivative’s Graph

Real “Real-life” Graph Reading

Open or Closed Should intervals of increasing, decreasing, or concavity be open or closed?

Others

Lin McMullin’s Theorem and More Gold The Golden Ratio in polynomials

Soda Cans Optimization video

Good Question 10 – The Cone Problem

Implicit Differentiation of Parametric Equations BC Topic

Here are links to the full list of posts discussing the ten units in the 2019 Course and Exam Description.

Limits and Continuity – Unit 1 (8-11-2020)

Definition of t he Derivative – Unit 2 (8-25-2020)

Differentiation: Composite, Implicit, and Inverse Function – Unit 3 (9-8-2020)

Contextual Applications of the Derivative – Unit 4 (9-22-2002) Consider teaching Unit 5 before Unit 4

Analytical Applications of Differentiation – Unit 5 (9-29-2020) Consider teaching Unit 5 before Unit 4 THIS POST

LAST YEAR’S POSTS – These will be updated in coming weeks

2019 – CED Unit 6 Integration and Accumulation of Change

2019 – CED Unit 7 Differential Equations Consider teaching after Unit 8

2019 – CED Unit 8 Applications of Integration Consider teaching after Unit 6, before Unit 7

2019 – CED Unit 9 Parametric Equations, Polar Coordinates, and Vector-Values Functions

2019 CED Unit 10 Infinite Sequences and Series