AP Questions Type 2: Linear Motion

We continue the discussion of the various type questions on the AP Calculus Exams with linear motion questions.

“A particle (or car, person, or bicycle) moves on a number line ….”

These questions may give the position equation, the velocity equation (most often), or the acceleration equation of something that is moving on the x– or y-axis as a function of time, along with an initial condition. The questions ask for information about motion of the particle: its direction, when it changes direction, its maximum position in one direction (farthest left or right), its speed, etc.

The particle may be a “particle,” a person, car, a rocket, etc. Particles don’t really move in this way, so the equation or graph should be considered to be a model. The question is a versatile way to test a variety of calculus concepts since the position, velocity, or acceleration may be given as an equation, a graph, or a table; be sure to use examples of all three forms during the review.

Many of the concepts related to motion problems are the same as those related to function and graph analysis (Type 3). Stress the similarities and show students how the same concepts go by different names. For example, finding when a particle is “farthest right” is the same as finding the when a function reaches its “absolute maximum value.” See my post for Motion Problems: Same Thing, Different Context for a list of these corresponding terms. There is usually one free-response question and three or more multiple-choice questions on this topic.

The position, s(t), is a function of time. The relationships are:

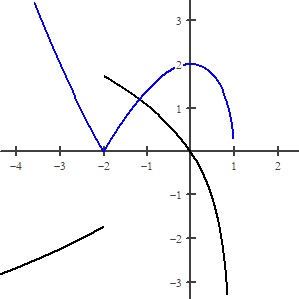

- The velocity is the derivative of the position,

. Velocity is has direction (indicated by its sign) and magnitude. Technically, velocity is a vector; the term “vector” will not appear on the AB exam.

- Speed is the absolute value of velocity; it is a number, not a vector. See my post for Speed.

- Acceleration is the derivative of velocity and the second derivative of position,

. It, too, has direction and magnitude and is a vector.

- Velocity is the antiderivative of the acceleration.

- Position is the antiderivative of velocity.

What students should be able to do:

- Understand and use the relationships above.

- Distinguish between position at some time and the total distance traveled during the time period.

- The total distance traveled is the definite integral of the speed (absolute value of velocity)

.

- Be sure your students understand the term displacement; it is the net distance traveled or distance between the initial position and the final position. Displacement, is the definite integral of the velocity (rate of change):

.

- The final position is the initial position plus the displacement (definite integral of the rate of change from x= a to x = t):

Notice that this is an accumulation function equation (Type 1).

- Initial value differential equation problems: given the velocity or acceleration with initial condition(s) find the position or velocity. These are easily handled with the accumulation equation in the bullet above, but may also be handled as an initial value problem.

- Find the speed at a given time. The speed is the absolute value of the velocity.

- Find average speed, velocity, or acceleration

- Determine if the speed is increasing or decreasing.

- If at some time, the velocity and acceleration have the same sign then the speed is increasing.If they have different signs the speed is decreasing.

- If the velocity graph is moving away from (towards) the t-axis the speed is increasing (decreasing). See the post on Speed.

- There is also a worksheet on speed here

- The analytic approach to speed: A Note on Speed

- Use a difference quotient to approximate the derivative (velocity or acceleration) from a table. Be sure the work shows a quotient.

- Riemann sum approximations.

- Units of measure.

- Interpret meaning of a derivative or a definite integral in context of the problem

Shorter questions on this concept appear in the multiple-choice sections. As always, look over as many questions of this kind from past exams as you can find.

This may be an AB or BC question. The BC topic of motion in a plane, (Type 8: parametric equations and vectors) will be discussed in a later post.

The Linear Motion problem may cover topics primarily from primarily from Unit 4, and also from Unit 3, Unit 5, Unit 6, and Unit 8 (for BC) of the 2019 CED.

Free-response examples:

- Equation stem 2017 AB 5,

- Graph stem: 2009 AB1/BC1,

- Table stem 2019 AB2

Multiple-choice examples from non-secure exams:

- 2012 AB 6, 16, 28, 79, 83, 89

- 2012 BC 2, 89