When I started this blog several years ago I was hoping my readers would ask questions that we could discuss or submit ideas for additional topics to write about. This has not really happened, but I’m still very open to the idea. (That was a HINT.) Since that first year when I had the entire curriculum ahead of me, I have written less not because I dislike writing, but because I am low on ideas.

The other day, I answered a question posted on the AP Calculus Community bulletin board about AB calculus exam question. It occurred to me that this somewhat innocuous looking question was quite good. So I decided to start an occasional series on good questions, from AP exams or elsewhere, that can be used to teaching beyond the actual things asked in the question. (My last post might be in this category, but that was written several months ago.)

In discussing these questions, I will make numerous comments about the question and how to take it further in your class. My idea is not just to show how to write a good answer, but rather to use the question to look deeper into the concepts involved.

Good Question #1: 2008 AB Calculus exam question 6.

The stem gave students the function . Students were also told that

.

- The first thought that occurs is why they gave the derivative. The reason is, as we will see, that the first derivative is necessary to answer the first three parts of the question. Therefore, a student who calculates an incorrect derivative is going to be in big trouble (and the readers may have a great deal of work to do reading with the student’s incorrect work). The derivative is calculated using the quotient rule, and students will have to demonstrate their knowledge of the quotient rule later in this question; there is no reason to ask them to do the same thing twice.

- If you are using this with a class, you can, and probably should, ask your students to calculate the first derivative. Then you can see how many giving the derivative would have helped.

- When discussing the stem, you should also discuss the domain, x > 0, and the x-intercept (1, 0). Other features of the graph, such as end behavior, are developed later in the question, so they may be put on hold briefly.

Part a asked students to write an equation of the tangent line at x = e2. To do this students need to do two calculations: and

. An equation of the tangent line is

.

- Writing the equation of a tangent line is a very important skill and should be straightforward. The point-slope form is the way to go. Avoid slope-intercept.

- The tangent line is used to approximate the value of the function near the point of tangency; you can throw in an approximation computation here.

- After doing part c, you should return here and discuss whether the approximation is an overestimate or an underestimate and how you can tell. (Answer: underestimate, since the graph is concave up here.)

- After doing part c, you can also ask them to write the tangent line at the point of inflection and whether approximations near the point of inflection are overestimates or an underestimates, and why. (Answer: Since the concavity change here, it depends on which side of the point of inflection the approximation is made. To the left is an overestimate; to the right is an underestimate.)

Part b asked students to find the x-coordinate of the critical point, determine whether it is a maximum, a minimum, or neither, and to “justify your answer.” To earn credit students had to write the equation and solve it getting x = e. They had to state that this is a maximum because “

changes from positive to negative at x = e.”

This is a very standard AP exam question. To expand it in your class:

- Discuss how you know the derivative changes sign here. This will get you into the properties of the natural logarithm function.

- Discuss why the change in sign tells you this is a maximum. (A positive derivative indicates an increasing function, etc.)

- After doing part c, you can return here and try the second derivative test.

- The question asks for “the” critical point, hinting that there is only one. Students should learn to pick up on hints like this and be careful if their computation produces more or less than one.

- At this point we have also determined that the function is increasing on the interval

and decreasing everywhere else. The question does not ever ask this, but in class this is worth discussing as important features of the graph. On why these are half-open intervals look here.

Part c told students there was exactly one point of inflection and asked them to find its x-coordinate. To do this they had to use the quotient rule to find that , set this equal to zero and find the x-coordinate to be x = e3/2.

- The question did not require any justification for this answer. In class you should discuss what a justification would look like. The reason is that the second derivative changes sign here. So now you need to discuss how you know this.

- Also, you can now determine that the function is concave down on the interval

and concave up on the interval

. Ask your class to justify this.

Part d asked student to find . The answer is

. While this seems almost like a throwaway tacked on the end because they needed another point, it is the reason I like this question.

- The question is easily solved:

.

- While tempting, the limit cannot be found by L’Hôpital’s Rule, because on substitution you get

,which is not one of the forms that L’Hôpital’s Rule can handle.

- The reason I like this part so much is that we have already developed enough information in the course of doing the problem to find this limit! The function is increasing and concave down on the interval

. Moving from the maximum to the left, the function crosses the x-axis at (1, 0), keeps heading south, and gets steeper. So the limit as you approach the y-axis from the right is negative infinity.This is the left-side end behavior.

- What about the right-side end behavior? (You ask your class.) Well, the function is positive and decreasing to the right of the maximum and becomes concave up after x = e3/2. Thus, it must flatten out and approach the x-axis as an asymptote.

- That

is clear from the note immediately above. This limit can be found by L’Hôpital’s Rule since it is an indeterminate of the type

. So,

.

- Notice also that the first derivative approaches zero as x approaches infinity. This indicates that the function’s graph approaches the horizontal as you travel farther to the right. The second derivative also approaches zero as x approaches infinity indicating that the function’s graph is becoming flatter (less concave).

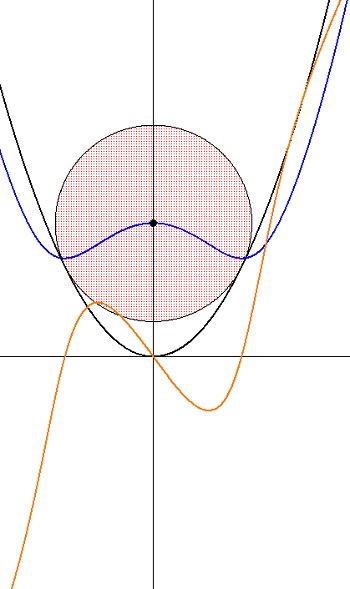

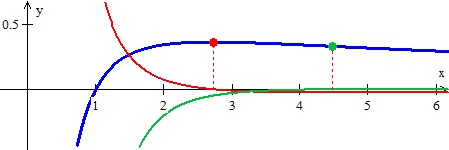

This question and the discussion is largely done analytically (working with equations). We did find a few important numbers in the course of the work. Hopefully, you students discussed this with many good words. To complete the Rule of Four, here is the graph.

And here is a close up showing the important features of the graph and the corresponding points on the derivatives.

The function is shown in blue, the derivative and maximum in red, and the second derivative and the point of inflection in green.

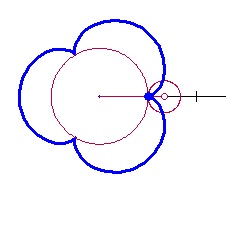

Finally, this function and the limit at infinity is similar to the more pathological example discussed in the post of October 31, 2012 entitled Far Out!