Third in the graphing calculator series.

In working up to the definition of the derivative you probably mention difference quotients. They are

The forward difference quotient (FDQ):

The backwards difference quotient (BDQ): , and

The symmetric difference quotient (SDQ):

Each of these is the slope of a (different) secant line and the limit of each as, if it exists, is the same and is the derivative of the function f at the point (x, f(x)). (We will assume h > 0 although this is not really necessary; if h < 0 the FDQ becomes the BDQ and vice versa.)

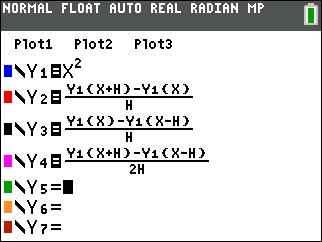

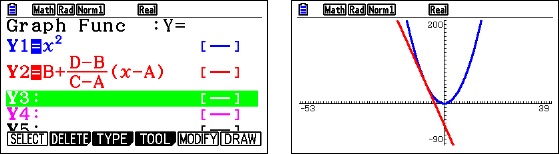

To see how this works you can graph a function and the three difference quotients on a graphing calculator. Here is how. Enter the function as the first function on your calculator and the difference quotients with it. Each of the difference quotients is defined in terms of Y1; this allows us to investigate the difference quotients of different functions by changing only Y1.

Now, on the home screen assign a value to h by typing [1] [STO] [alpha] [h]

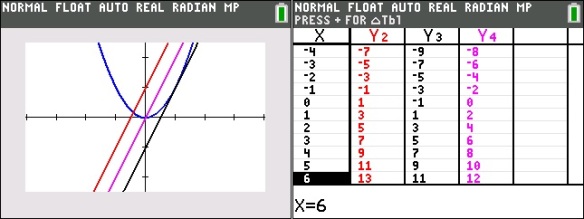

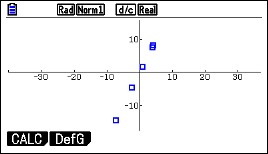

Graph the result in a square window.

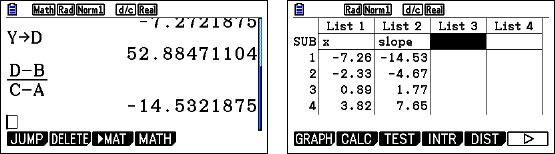

The look at the table screen. (Y1 has been turned off). Can you express Y2, Y3, and Y4 in term of x?

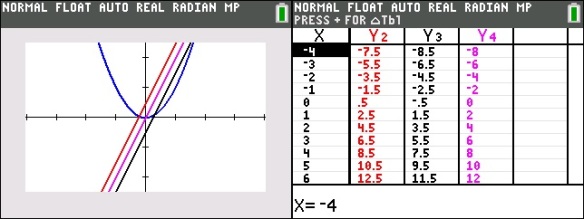

Then change h by storing a different value, say ½, to h and graph again. Then look at the table screen again. Can you express Y2, Y3, and Y4 in term of x?

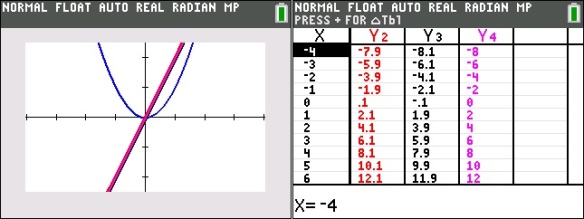

Then graph again with h = -0.1

As you can see as h gets smaller (h 0), the three difference quotients are FDQ: 2x + h, the BDQ is 2x – h, and the SDQ is 2x. They converge to the same thing. The limit of each difference quotient as h approaches zero is twice the x coordinate of the point. If you’re not sure try a smaller value of h.

The function to which each of these converge is called the derivative of the original function (Y1). In the example the derivative of x2 is 2x.

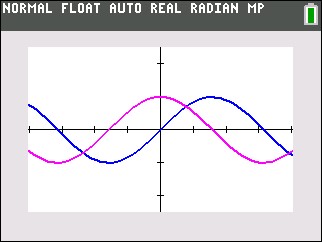

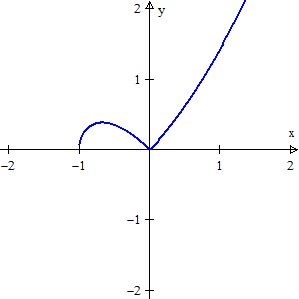

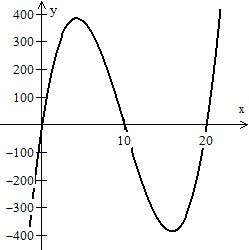

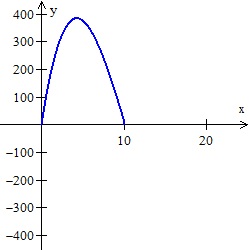

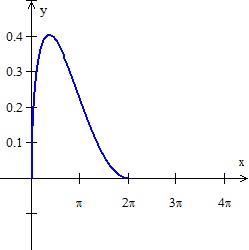

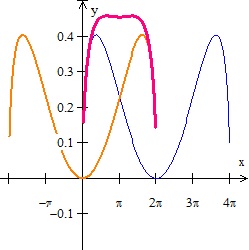

Now try another function say, Y1 = sin(x) and repeat the graphs and tables above. The tables will probably not be of much help, since the pattern is not familiar. The graph shows the function (dark blue) and only the SDQ (light blue), h = 0.1 Can you guess what the derivative might be?

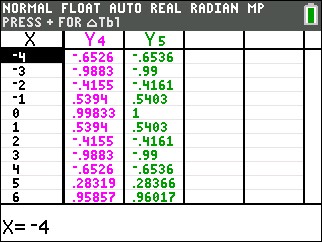

I f you guessed cos(x) you are correct. The table shows the SDQ values as Y4, and the values of cos(x) as Y5. Pretty close! If you want to get closer try h = 0.001.

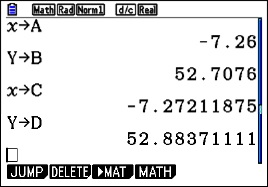

If you have a CAS calculators such as the TI-Nspire or the HP PRIME you can do this activity with sliders. Also you may try this with DESMOS. Click here or on the graph below. Some interesting functions to start with are cos(x) and | x |.

And by the way, the SDQ is what most graphing calculators use to calculate the derivative. It is called nDeriv on TI calculators.