The Definition of the Definite Integral.

The definition of the definite integrals is: If f is a function continuous on the closed interval [a, b], and is a partition of that interval, and

, then

The left side of the definition is, of course, any Riemann sum for the function f on the interval [a, b]. In addition to being shorter, the right side also tells you about the interval on which the definite integral is computed. The expression is called the “norm of the partition” and is the longest subinterval in the partition. Usually, all the subintervals are the same length,

, and this is the last you will hear of the norm. With all the subdivisions of the same length this can be written as

Other than that, there is not much more to the definition. It is simply a quicker and more efficient notation for the sum.

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus (FTC).

First recall the Mean Value Theorem (MVT) which says: If a function is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and differentiable on the open interval (a, b) then there exist a number, c, in the open interval (a, b) such that .

Next, let’s rewrite the definition above with a few changes. The reason for this will become clear.

Since every function is the derivative of another function (even though we may not know that function or be able to write a closed-form expression for it), I’ve expressed the function as a derivative, I’ve also chosen the point in each subinterval, , to be the number in each subinterval guaranteed by the MVT for that subinterval.

Then, . Making this substitution, we have

And since and

,

This equation is called the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus. In words, it says that the integral of a function can be found by evaluating the function of which the integrand is the derivative at the endpoints of the interval and subtracting the values. This is a number that may be positive, negative, or zero depending on the function and the interval. The function of which the integrand is the derivative, is called the antiderivative of the integrand.

The real meaning and use of the FTC is twofold:

- It says that the integral of a rate of change (i.e. a derivative) is the net amount of change. Thus, when you want to find the amount of change – and you will want to do this with every application of the derivative – integrate the rate of change.

- It also gives us an easy way to evaluate a Riemann sum without going to all the trouble that is necessary with a Riemann sum; simply evaluate the antiderivative at the endpoints and subtract.

At this point I suggest two quick questions to emphasize the second point:

- Find

.

Ask if anyone knows a function whose derivative is 2x? Your students will know this one. The answer is x2, so

.

Much easier than setting up and evaluating a Riemann sum!

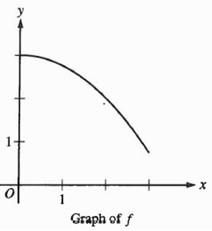

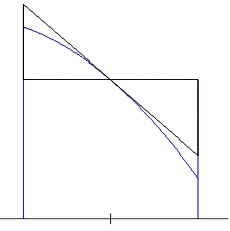

2. Then ask your students to find the area enclosed by the coordinate axes and the graph of cos(x) from zero to . With a little help they should arrive at

.

Then ask if anyone knows a function whose derivative is cos(x). it’s sin(x), so

.

At this point they should be convinced that the FTC is a good thing to know.

There is another form of the FTC that is discussed in More About the FTC.