Two of nine. Continuing the series started in my last post, this post looks at the AB Calculus 2021 exam question AB 2. The series looks at each question with the aim of showing ways to use the question in with your class as is or by adapting and expanding it. Like most of the AP Exam questions there is a lot more you can ask from the stem and a lot of other calculus you can discuss.

2021 AB 2

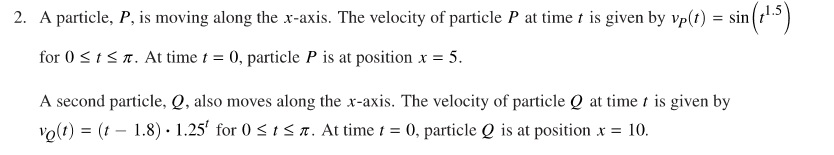

This is a Linear Motion Problem (Type 2) and has topics from Unit 4 of the current Course and Exam Description. Two particles are moving on the x-axis and the questions ask about their motion individually and relative to each other. The velocity and initial position are given for each particle. Parts (a), (c), and (d) are typical; (b) is the core of the problem.

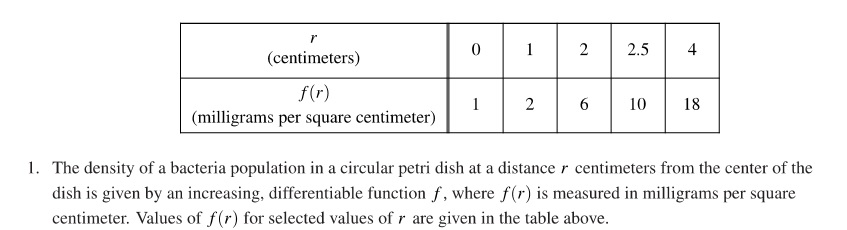

The stem is:

Part (a): Students are asked to find the position of each particle at time t = 1.

Discussion and ideas for adapting this question:

- The expected approach is to calculate for each particle the initial position plus the displacement from t = 0 to t = 1. So, for P the computation is

and similarly for Q(1). This is a calculator allowed question and students should use their calculator to find the answer and not do it by hand.

- A different approach is to work it as an initial value differential equation problem. This will work but takes longer than the approach suggested above.

- In class, it is worth discussing both methods.

- You can adapt this by using a different time.

- Another question is to find (only) the displacement if each particle over some time interval. Displacement has been asked in other years.

- Ask “Will the particles ever collide? If so when and justify your answer. (Answer: no)

Part (b): Students were asked to determine if the particles are moving apart or towards each other at time t = 1. This is the main question and requires a careful analysis of their motion.

Discussion and ideas for adapting this question:

- To determine this, students need to consider the velocity of the particles and their position (from part (a)). P is to the left of Q and moving right. Q is to the right of P and moving left, therefore, the distance between them is decreasing.

- You can practice this analysis by using different times.

- Ask students to carefully describe the motion of one or both particles: when it is moving left and right, when it changes direction, find the local maximum and minimum positions, etc. Notice that this is really the same as analyzing the shape of a graph. The connection between the two problems will help students understand both better. See: Motion Problems: Same Thing, Different Context

Part (c): A question about speed.

Discussion and ideas for adapting this question:

- A typical question. Students should compare the signs of the velocity and acceleration of the particle. If they are the same, the speed is increasing; if different, decreasing.

- You may ask this of the other particle.

- You may ask this at different times.

- See previous posts on speed here and here.

Part (d): Students were required to find the total distanced traveled by Q on the interval [0, π].

Discussion and ideas for adapting this question:

- Since speed is the absolute value of the velocity, integrate the absolute value of the velocity. Do this on a calculator.

- Adapt this by using a different interval.

- Adapt this by using the other particle.

- Another (longer) way to approach this question is to find where the particle changes direction by finding where the velocity changes from negative to positive and/or vice versa (i.e., the local extreme values). Then find the distanced traveled on each part of the “trip,” and add or subtract. This will reinforce a lot of the concepts involved in linear motion; that is why it is worth doing. As for the exam, integrating the absolute value is the way to go. However, if this were a non-calculator question, then it would have to be done this way. Find a simpler velocity and try it both ways.

- To integrate the absolute value by hand, it is necessary to break the interval into subintervals depending on where the velocity is positive or negative. This is the same as the approach in the bullet immediately above. This, too, is worth showing to reinforce the definition of absolute value.

2021 revised as an in-out question.

There was some unhappiness over the fact that the 2021 AB Calculus exam did not have an in-out questions (Rate and Accumulation Type 1). However, this question does have two rates going in opposite directions. So, just to be ornery, I rewrote it as an in-out questions by changing the context and units while keeping the same velocity functions. The point is that the situation tested can be reframed in other ways. Seeing the same thing in different dress may help students concentrate on the calculus involved. Here it is:

A factory processes cement at the rate of tons per hour for

hours. At time t = 0 the amount on hand is P = 5 tons.

The factory ships the cement at a rate given by tons per hour for

hours. At time t = 0 the amount shipped is 10 tons.

- Find the amount processed and the amount shipped after hour.

- Is the amount on hand increasing or decreasing at time t = 1? Explain your reasoning.

- At what rate is the rate at which the cement is being shipped changing at t = 1? Is the amount being shipped increasing or decreasing at t = 1? Explain your reasoning.

- Find the total amount of cement processed over the time interval

.

Next week 2021 AB 3/ BC 3.

I would be happy to hear your ideas for other ways to use this questions. Please use the reply box below to share your ideas.