My choices for the Good Question series are somewhat eclectic. Some are chosen because they are good, some because they are bad, some because I learned something from them, some because they can be extended, and some because they can illustrate some point of mathematics. This question and the next, Good Question 16, are in the latter group. They both concern units. They both are taken from this year’s AP calculus BC exam; both are suitable for AB classes. In this question 2018 BC 2(a) has some unusual units and in the next 2018 BC 2(b) the units help you figure out what to do. Part (c) concerns an improper integral and pard (d) is about parametric equation, neither of these are AB topics.

2018 BC 2(a)

2018 BC 2 gave an equation that modeled the density p(h) of plankton in a sea in units of millions of cells per cubic meter, as a function of the depth, h, in meters. Specifically,  for

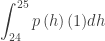

for  . Part (a) asked for the value of

. Part (a) asked for the value of  and also asked students “Using correct units, [to] interpret the meaning of

and also asked students “Using correct units, [to] interpret the meaning of  in the context of the problem.”

in the context of the problem.”

Plankton

This was a calculator active question, so the computation is easy enough:

Now units of the derivative are always very easy to determine; this should be automatic. The derivative is the limit of a difference quotient, so its units are the units of the numerator divided by the units of the denominator. In this case that’s millions of cells per cubic meter per meter of depth.

While “millions of cells per meter to the fourth power” is technically correct and will probably earn credit, what is a meter to the fourth power?

It is similar to the better-known situation with velocity and acceleration. I never liked the idea of saying the acceleration is so many meters per square second. What’s a square second? Are there round seconds? Acceleration is the change in velocity in meters per second per second; that is, at a particular time the velocity is changing at the rate of so-many meters per second each second.

-

-

Square Seconds?

-

-

Round Seconds?

Returning to the question, a cubic meter (volume) and a meter of depth (linear) are not things that you should combine. The notational convenience of writing meters to the fourth power hides the true meaning. So, a better interpretation is “At depth of 25 meters, the number cells is decreasing at the rate of 1.179 million cells per cubic meter per meter of depth.” or “The number of cells changing at the rate of -1.179 million cells per cubic meter per meter of depth.”

Had the model been given using volume units such as millions of cells per liter, then the units of the derivative would be millions of cells per liter per meter. That makes more sense.

But what does it mean?

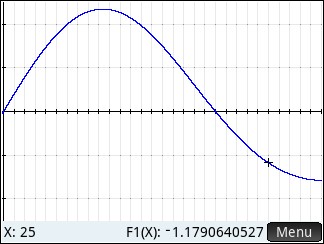

Let’s look at the graph of the derivative. The window is 0 < h < 30 and –2.5 < p(x) < 2.5

It means, that as we pass thru that thin (thickness  ) film of water 25 meters down, there are approximately 1.179 million cells per cubic meter less than in the thin film right above it and more than in the thin film right below it.

) film of water 25 meters down, there are approximately 1.179 million cells per cubic meter less than in the thin film right above it and more than in the thin film right below it.

For reference,  million cells per cubic meter. Of course, that thin (thickness

million cells per cubic meter. Of course, that thin (thickness  ) film of water has very little volume; it is kind of difficult to think of a cubic meter exactly 25 meters below the surface (maybe a cube extending from 24.5 meters to 25.5 meters?). As

) film of water has very little volume; it is kind of difficult to think of a cubic meter exactly 25 meters below the surface (maybe a cube extending from 24.5 meters to 25.5 meters?). As  does a cubic meter approach a square meter?

does a cubic meter approach a square meter?

The cubic meter above h = 25 has  cells and the cubic meter below has 25.586 million cells. This is a decrease of 1.1767 million cells. So, the derivative is reasonable.

cells and the cubic meter below has 25.586 million cells. This is a decrease of 1.1767 million cells. So, the derivative is reasonable.

(To make the units of  correct, I included a factor of 1 square meter, this multiplied by p(h) million cells per cubic meter and by dh in meters give a result of millions of cells. More on why this is necessary in Good Question 16 on density.)

correct, I included a factor of 1 square meter, this multiplied by p(h) million cells per cubic meter and by dh in meters give a result of millions of cells. More on why this is necessary in Good Question 16 on density.)

Previous Good Questions can be found under the “Thru the Year” tab on the black navigation bar at the top of the page, or here.