This and the next several posts will be about graphing and specifically how the function and its first and second derivatives are related. Since I do not intend this to be a textbook, I will not be doing textbook stuff. Rather, I hope to add some big picture things about the concepts involved. Hope you find it useful.

________________________________

Graphs of functions come in some combination of five shapes:

• Linear,

• Increasing, concave up,

• Increasing, concave down,

• Decreasing, concave up, and

• Decreasing, concave down.

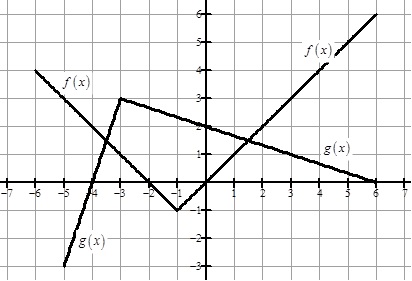

I have put together an activity, An Exploration of the Shape of a Graph, to help students learn the relationship between the shapes and the derivative. Leaving the linear sections aside, the idea of the activity is to call students’ attention to the other four shapes and the slope of the tangent line (the derivative) in the intervals where the graph has each shape.

The key is to keep focused on the tangent line. To this end I suggest drawing short tangent segments parallel to the graph, as illustrated in the figure below.

Air-graphing: Another way to help students internalize this idea is to draw the graph of a function on the board and then have the students hold their pen out in front of them so the pen looks like a segment tangent to the graph. Then move the pen along the graph paying attention to the slope.

Either way what you want students to be aware of is

(1) Where the slopes are positive and where they are negative. This will later be related to the intervals where the function increases and decreases, and

(2) How the slope itself is changing. Is the slope increasing or decreasing? This will later be related to the concavity.

I hope you and your students find this activity helpful.