The sixth in the Graphing Calculator / Technology series

The topic of integration is coming up soon. Here are some notes and ideas about the integration operation on graphing calculators. The entries are the same or very similar for all calculator brands.

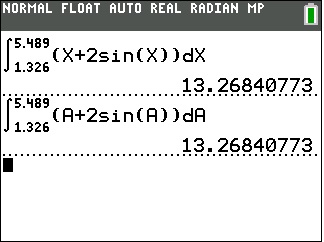

The basic problem of evaluating a definite integral on a graphing calculator is done without finding an antiderivative; that is, the calculator uses a numerical algorithm to produce the result. The calculator provides a template, and you fill in the 4 squares so that the expression looks exactly like what you write by hand. Then the calculator computes the result. (Older models require a one-line input requiring, in order, the integrand, the independent variable, the lower limit of integration and the upper limit in that order, separated by commas.) The first interesting thing is that the variable in the integrand does to have to be x. As the first figure illustrates using x or a or any other letter gives the same result.

and you fill in the 4 squares so that the expression looks exactly like what you write by hand. Then the calculator computes the result. (Older models require a one-line input requiring, in order, the integrand, the independent variable, the lower limit of integration and the upper limit in that order, separated by commas.) The first interesting thing is that the variable in the integrand does to have to be x. As the first figure illustrates using x or a or any other letter gives the same result.

This is because the variable of integration is just a place holder. Sometimes called a “dummy variable”, this letter can be anything at all, including x. On the home or calculation screen you might as well always use x, so the entry will look like what you have on your paper. As we will see, when graphing it may be less confusing to use a different letter.

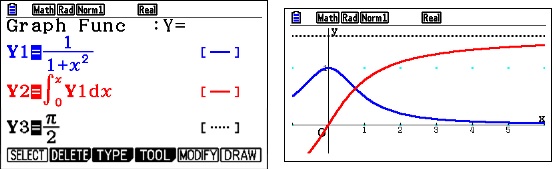

The antiderivative, F, of any function, f, can be written as a function defined by an integral where there is a point on the antiderivative of f , which is with F ’ = f. The point (a, F(a)) is the initial condition. (In the following we will use F(a) = 0 as the initial condition – the graph will contain the origin. As a further investigation, try changing the lower limit to different numbers and see how that changes the graph.)

The integration operation can be used to graph the antiderivative of a function without finding the antiderivative. You may graph the antiderivative when teaching antiderivatives. Have students look at the graph of the antiderivative and guess what that function is.

When graphing use x as the upper limit of integration and a different letter for the variable in the rest of the template. The calculator will use different values of x to calculate the points to be graphed.

The set-up shown in the next figure shows how to enter a function defined by an integral (blue line) and the same function obtained by antidifferentiating (red squares). As you can see the results are the same.

In this way, you can explore the functions and their indefinite integrals by graphing.

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

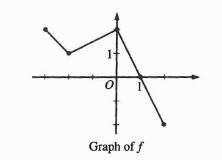

Another use of using the graph of an integral is to investigate both parts of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus (FTC). Roughly speaking, the FTC says that the integral of a derivative of a function is that function, and the derivative of an integral is the integrand.

In the figure below, the same function is entered both ways; the graphs are the same. (Note the x’s in the second line must be x in all four places.)

.