A fairly common max/min problem asks the student to find the point on the parabola  that is closest to the point

that is closest to the point  . The solution is not too difficult. The distance, L(x), between A and the point

. The solution is not too difficult. The distance, L(x), between A and the point  on the parabola is given by

on the parabola is given by

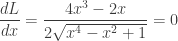

And the minimum distance can be found when

This occurs when  . The local maximum is occurs when x = 0. The (global) minimums are the other two values located symmetrically to the y-axis.

. The local maximum is occurs when x = 0. The (global) minimums are the other two values located symmetrically to the y-axis.

_________________________

Somewhere I saw this problem posed in terms of a marble dropped into a vase shaped like a parabola. So I think of it that way. This accounts for the title of the post. The problem is, however, basically a two-dimensional situation.

In this post I would like to expand and explore this problem. The exploration will, I hope, give students some insight and experience with extreme values, and the relationship between a graph and its derivative. I will pose a series of questions that you could give to your students to explore. I will answer the questions as I go, but you, of course, should not do that until your students have had some time to work on the questions.

Graphing technology and later Computer Algebra Systems (CAS) will come in handy.

_________________________

1. Consider a general point  on the y-axis. Find the x-coordinates of the closest point on the parabola in terms of a.

on the y-axis. Find the x-coordinates of the closest point on the parabola in terms of a.

The distance is now given by

And  when

when

The (local) maximum is at x = 0. The other values are the minimums. The CAS computation is shown at the end of the post. This is easy enough to do by hand.

2. Discuss the equation  in relation to this situation.

in relation to this situation.

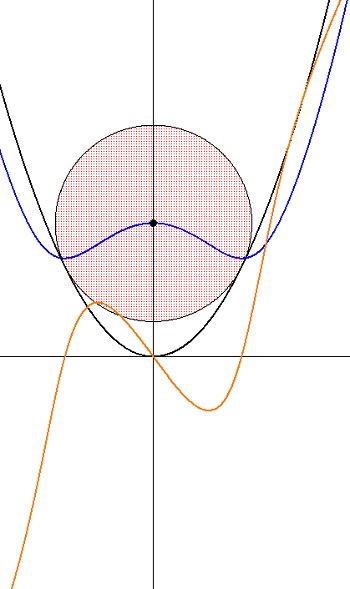

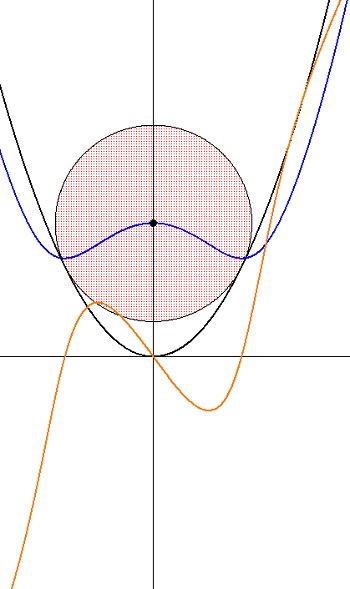

This is the equation of a circle with center at A with radius of L. At the minimum distance this circle will be tangent to the parabola.

3. What happens when  and when

and when  ?

?

When  , the three zeroes are the same. The circle is tangent to the parabola at the origin and a is the minimum distance.

, the three zeroes are the same. The circle is tangent to the parabola at the origin and a is the minimum distance.

When  , the circle does not intersect the parabola. Notice that in this case two of the roots of

, the circle does not intersect the parabola. Notice that in this case two of the roots of  are not Real numbers.

are not Real numbers.

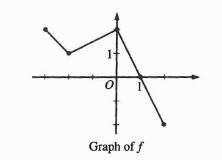

4. Consider the distance, L(x), from point A to the parabola. As x moves from left to right describe how this length changes. Be specific. Sketch the graph of this distance y = L(x). Where are its (local) maximum and minimum values, relative to the parabola and the circle tangent to the parabola?

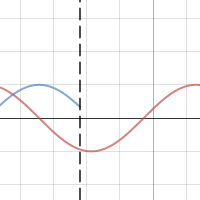

The clip below illustrates the situation. The two segments marked L(x) are congruent. The graph of y = L(x) is a“w” shape similar to but not quartic polynomial. The minimums occur directly under the points of tangency of the circle and the parabola. The local maximum is directly over the origin. Is it coincidence that the graph goes through the center of the circle? Explain.

5. Graph

5. Graph  and compare its graph with the graph of

and compare its graph with the graph of

L(x) is the blue graph and and L'(x) is the orange graph.

Notice the concavity of L'(x)

6. The graph of  appears be concave up, then down, then (after passing the origin) up, and then down again. There are three points of inflection. Find their x-coordinates in terms of a. How do these points relate to y = L(x) ? (Use a CAS to do the computation)

appears be concave up, then down, then (after passing the origin) up, and then down again. There are three points of inflection. Find their x-coordinates in terms of a. How do these points relate to y = L(x) ? (Use a CAS to do the computation)

The points of inflection of the derivative can be found from the second derivative of the derivative (the third derivative of the L(x)). The abscissas are  . The CAS computation is shown below

. The CAS computation is shown below

CAS Computation for questions 1 and 6.