About this time of year you find someone, hopefully one of your students, asking, “If I’m finding where a function is increasing, is the interval open or closed?”

Do you have an answer?

This is a good time to teach some things about definitions and theorems.

The place to start is to ask what it means for a function to be increasing. Here is the definition:

A function is increasing on an interval if, and only if, for all (any, every) pairs of numbers x1 < x2 in the interval, f(x1) < f(x2).

(For decreasing on an interval, the second inequality changes to f(x1) > f(x2). All of what follows applies to decreasing with obvious changes in the wording.)

- Notice that functions increase or decrease on intervals, not at individual points. We will come back to this in a minute.

- Numerically, this means that for every possible pair of points, the one with the larger x-value always produces a larger function value.

- Graphically, this means that as you move to the right along the graph, the graph is going up.

- Analytically, this means that we can prove the inequality in the definition.

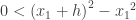

For an example of this last point consider the function f(x) = x2. Let x2 = x1 + h where h > 0. Then in order for f(x1) < f(x2) it must be true that

This can only be true if  , Thus, x2 is increasing only if

, Thus, x2 is increasing only if  .

.

Now, of course, we rarely, if ever, go to all that trouble. And it is even more trouble for a function that increases on several intervals. The usual way of finding where a function is increasing is to look at its derivative.

Notice that the expression  looks a lot like the numerator of the original limit definition of the derivative of x2 at x = x1, namely

looks a lot like the numerator of the original limit definition of the derivative of x2 at x = x1, namely  . If h > 0, where the function is increasing the numerator is positive and the derivative is positive also. Turning this around we have a theorem that says, If

. If h > 0, where the function is increasing the numerator is positive and the derivative is positive also. Turning this around we have a theorem that says, If  for all x in an interval, then the function is increasing on the interval. That makes it much easier to find where a function is increasing: we simplify find where its derivative is positive.

for all x in an interval, then the function is increasing on the interval. That makes it much easier to find where a function is increasing: we simplify find where its derivative is positive.

There is only a slight problem in that the theorem does not say what happens if the derivative is zero somewhere on the interval. If that is the case, we must go back to the definition of increasing on an interval or use some other method. For example, the function x3 is increasing everywhere, even though its derivative at the origin is zero.

Let’s consider another example. The function sin(x) is increasing on the interval ![\left[ -\tfrac{\pi }{2},\tfrac{\pi }{2} \right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B+-%5Ctfrac%7B%5Cpi+%7D%7B2%7D%2C%5Ctfrac%7B%5Cpi+%7D%7B2%7D+%5Cright%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) (among others) and decreasing on

(among others) and decreasing on ![\left[ \tfrac{\pi }{2},\tfrac{3\pi }{2} \right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B+%5Ctfrac%7B%5Cpi+%7D%7B2%7D%2C%5Ctfrac%7B3%5Cpi+%7D%7B2%7D+%5Cright%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . It bothers some that

. It bothers some that  is in both intervals and that the derivative of the function is zero at x =

is in both intervals and that the derivative of the function is zero at x =  . This is not a problem. Sin(

. This is not a problem. Sin( ) is larger than all the other values is both intervals, so by the definition, and not the theorem, the intervals are correct.

) is larger than all the other values is both intervals, so by the definition, and not the theorem, the intervals are correct.

It is generally true that if a function is continuous on the closed interval [a,b] and increasing on the open interval (a,b) then it must be increasing on the closed interval [a,b] as well. (There is a proof by Lou Talman of this fact click here .)

Returning to the first point above: functions increase or decrease on intervals not at points. You do find questions in books and on tests that ask, “Is the function increasing at x = a.” The best answer is to humor them and answer depending on the value of the derivative at that point. Since the derivative is a limit as h approaches zero, the function must be defined on some interval around x = a in which h is approaching zero. So answer according to the value of the derivative on that interval.

You can find more on this here.

Case Closed.

and then rewrite this as

. Differentiating this gives

.

and

.

. The domain of this function is

and the range is

, the function is increasing on both parts of its domain; we will need to know this.

.

is increasing and the derivative should always be positive. So, this needs to be adjusted to