Good Question 11 – or not.

The question below appears in the 2016 Course and Exam Description (CED) for AP Calculus (CED, p. 54), and has caused some questions since it is not something included in most textbooks and has not appeared on recent exams. The question gives a Riemann sum and asks for the definite integral that is its limit. Another example appears in the 2016 “Practice Exam” available at your audit website; see question AB 30. This type of question asks the student to relate a definite integral to the limit of its Riemann sum. These are called reversal questions since you must work in reverse of the usual order. Since this type of question appears in both the CED examples and the practice exam, the chances of it appearing on future exams look good.

To the best of my recollection the last time a question of this type appeared on the AP Calculus exams was in 1997, when only about 7% of the students taking the exam got it correct. Considering that by random guessing about 20% should have gotten it correct, this was a difficult question. This question, the “radical 50” question, is at the end of this post.

Example 1

Which of the following integral expressions is equal to  ?

?

There were 4 answer choices that we will consider in a minute.

The first key to answering the question is to recognize the limit as a Riemann sum. In general, a right-side Riemann sum for the function f on the interval [a, b] with n equal subdivisions, has the form:

To evaluate the limit and express it as an integral, we must identify, a, b, and f. I usually begin by looking for  . Here

. Here  and from this conclude that b – a = 1, so b = a + 1.

and from this conclude that b – a = 1, so b = a + 1.

Usually, you can start by considering a = 0 , which means that the  becomes the “x.”. Then rewriting the radicand as

becomes the “x.”. Then rewriting the radicand as  , it appears the function is

, it appears the function is  and the limit is

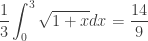

and the limit is  .

.

The answer choices are

(A)  (B)

(B)  (C)

(C)  (D)

(D)

The correct choice is (A), but notice that choices B, C, and D can be eliminated as soon as we determine that b = a + 1. That is not always the case.

Let’s consider another example:

Example 2:

As before consider  , which implies that b = a + 3. With a = 0, the function appears to be

, which implies that b = a + 3. With a = 0, the function appears to be  on the interval [0, 3], so the limit is

on the interval [0, 3], so the limit is

BUT

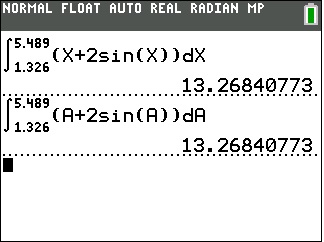

What if we take a = 2? If so, the limit is  .

.

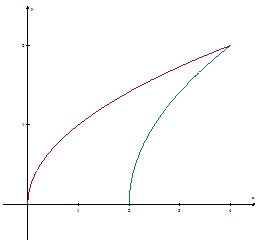

And now one of the “problems” with this kind of question appears: the answer written as a definite integral is not unique!

Not only are there two answers, but there are many more possible answers. These two answers are horizontal translations of each other, and many other translations are possible, such as  .

.

The same thing can occur in other ways. Returning to example 1,and using something like a u-substitution, we can rewrite the original limit as  .

.

Now b = a + 3 and the limit could be either  or

or  , among others.

, among others.

My opinions about this kind of question.

The real problem with the answer choices to Example 1 is that they force the student to do the question in a way that gets one of the answers. It is perfectly reasonable for the student to approach the problem a different way, and get a different correct answer that is not among the choices. This is not good.

The problem could be fixed by giving the answer choices as numbers. These are the numerical values of the 4 choices:(A) 14/9 (B) 14/3 (C) 14/3 (D)  . As you can see that presents another problem. Distractors (wrong answers) are made by making predictable calculus mistakes. Apparently, two predictable mistakes give the same numerical answer; therefore, one of them must go.

. As you can see that presents another problem. Distractors (wrong answers) are made by making predictable calculus mistakes. Apparently, two predictable mistakes give the same numerical answer; therefore, one of them must go.

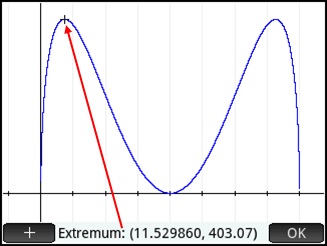

A related problem is this: The limit of a Riemann sum is a number; a definite integral is a number. Therefore, any definite integral, even one totally unrelated to the Riemann sum, which has the correct numerical value, is a correct answer.

I’m not sure if this type of question has any practical or real-world use. Certainly, setting up a Riemann sum is important and necessary to solve a variety of problems. After all, behind every definite integral there is a Riemann sum. But starting with a Riemann sum and finding the function and interval does not seem to me to be of practical use.

The CED references this question to MPAC 1: Reasoning with definitions and theorems, and to MPAC 5: Building notational fluency. They are appropriate,and the questions do make students unpack the notation.

My opinions notwithstanding, it appears that future exams will include questions like these.

These questions are easy enough to make up. You will probably have your students write Riemann sums with a small value of n when you are teaching Riemann sums leading up to the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus. You can make up problems like these by stopping after you get to the limit, giving your students just the limit, and having them work backwards to identify the function(s) and interval(s). You could also give them an integral and ask for the associated Riemann sum. Question writers call questions like these reversal questions since the work is done in reverse of the usual way.

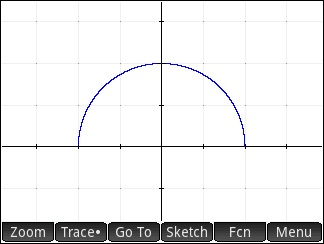

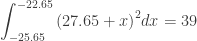

Here is the question from 1997, for you to try. The answer is below.

Answer B. Hint n = 50

Revised 5-5-2022

Someone asked me about this a while ago and I thought I would share it with you. It may be a good question to get your students thinking about; see if they can give a definitive answer that will, of course, include a justification.

Someone asked me about this a while ago and I thought I would share it with you. It may be a good question to get your students thinking about; see if they can give a definitive answer that will, of course, include a justification.. Then