Cubic Symmetry

Some things are fairly obvious. For example, if you look at the graphs of a few cubic equations, you might think that each is symmetric to a point and on closer inspection the point of symmetry is the point of inflection.

This is true and easy to prove. You can find the point of inflection, and then show that any point a certain distance horizontally on one side is the same distance above (or below) the point of inflection as a point the same distance horizontally on the other side is below (or above). Another way is to translate the cubic so that the point of inflection is at the origin and then show the resulting function is an odd function (i.e. symmetric to the origin).

But some other properties are not at all obvious. How someone thought to look for them is not even clear.

Tangent Line.

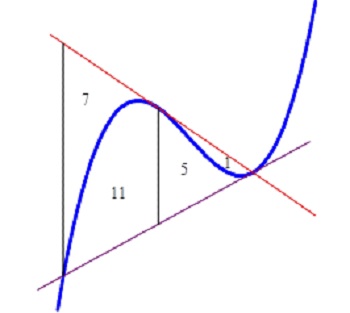

If you have cubic function with real roots of x = a, x = b, and x = c not necessarily distinct, if you draw a tangent line at a point where x is the average of any two roots, x = ½(a + b), , then this tangent line intersects the cubic on the x-axis at exactly the third root, x = c. Here is a Desmos graph illustrating this idea.

Here is a proof done with a CAS. The first line is a cubic expressed in terms of its roots. The third line asks where the tangent line at x = m intersects the x-axis. The last line is the answer: x = c or whenever a = b (i.e. when the two roots are the same, in which case the tangent line is the x-axis and of course also contains x = c.

Areas

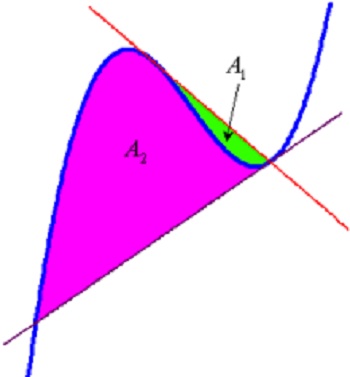

Even harder to believe is this: Draw a tangent line anywhere on a cubic. This tangent will intersect the cubic at a second point and the line and the cubic will define a region whose area is A1. From the second point draw a tangent what intersects the cubic at a third point and defines a region whose area is A2. The ratio of the areas A2/A1 = 16. I have no idea why this should be so, but it is.

Here is a proof, again by CAS: The last line marked with a square bullet is the computation of the ratio and the answer, 16, is in the lower right,

And if that’s not strange enough, inserting two vertical lines defines other regions whose areas are in the ratios shown in the figure below.

Who’d a thunk it?

.