Antiderivatives are needed to evaluate definite integrals.

The next thing to consider is how to find antiderivatives.

Each of the formulas you learned for finding a derivative may be reversed to find antiderivatives. For example, since , it follows that.

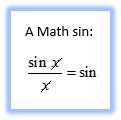

I wish it were all that simple.

There are three concerns.

First, if the original function included a constant, this constant will disappear when you differentiate. Think about it: adding a constant translates the graph up or down but does not change the shape; the slope (derivative) remains the same.

This means that a function has an infinite number of antiderivatives. The good news is they are all the same except for the constant of integration.

The is the derivative of

and all kinds of similar things.

To remind you of this you should write where C is a constant, a number, called the constant of integration.

Next, very similar looking functions have very different antiderivatives found in very different ways. I won’t scare you with examples, you’ll see them soon enough.

Finally, there are many simple looking functions, that you can easily differentiate that do not have an antiderivative that is any function you’ve seen.

In the last parts of Unit 6, you will learn some methods integration. BC students will learn a few additional methods. You’ve only scratched the surface: there are many more, but these can wait until you get to university (or maybe Mathematica knows them – I wouldn’t be surprised).

As you learn these methods of integration you will have to decide when to use each. Learn which method is appropriate in each situation.

Course and Exam Description Unit 6.8 thru 6.14