Mathematics more often tends to delight when it exhibits an unanticipated result rather than conforming to … expectations. In addition, the pleasure derived from mathematics is related in many cases to the surprise felt upon the perception of totally unexpected relationships and unities.

– Mario Livio, The Golden Ratio

I have a theorem named after me. I did not name it, but I did prove it – well more like I tripped over it. It is a calculus related idea. Here is how it came about. I say “came about” because as you will see I did not set out to prove it. I just sort of fell in my lap as I was working on something else.

I was trying to do an animation of an idea that I had heard about: If you have a fourth degree, or quartic, polynomial with a “W” shape it has two points of inflection. If you draw a line through the points of inflection three regions enclosed by the line and the polynomial’s graph are formed. The areas of these regions are in the ratio of 1:2:1. In order to make the animation work I needed the general coordinates of the four points where the line intersects the quartic.

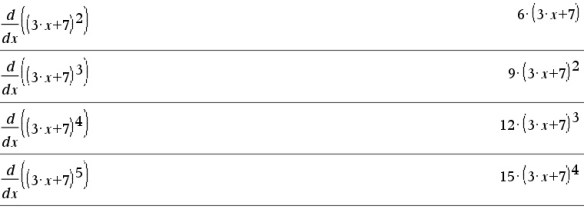

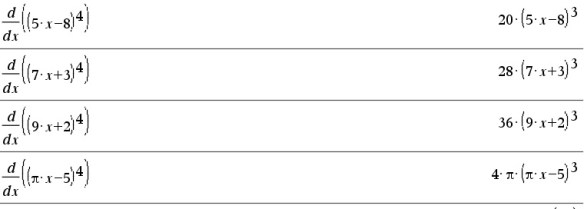

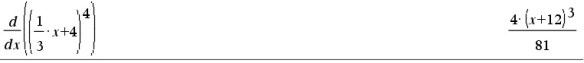

The straightforward way to proceed would be to write a general fourth degree polynomial,

differentiate it twice to find the second derivative. Then find the zeros of the second derivative (by the quadratic formula), write the equation of the line through them, and then find where else the line intersects the quartic. Without even starting I realized that even with a CAS the algebra and equation solving was going to be really fun (Not!). So, I decided on an alternative approach.

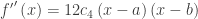

I decided to let the zeros of the second derivative be x = a and x = b, then at least they would be easy to work with. Then the second derivative is  where the

where the  is the leading coefficient of the quartic and the 12 comes from differentiating twice.

is the leading coefficient of the quartic and the 12 comes from differentiating twice.

I integrated to get the first derivative and added  , the coefficient of the linear term, as the constant of integration. I integrated again and added

, the coefficient of the linear term, as the constant of integration. I integrated again and added  , the constant term. as the constant of integration. This resulted in the original quartic function:

, the constant term. as the constant of integration. This resulted in the original quartic function:

Then I wrote the equation of y(x) the line through the points of inflection. It is too long to copy, but you may see it in the screen capture at the end of the post. (That is what is nice about a CAS: you really do not have to worry about how complicated things are.)

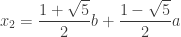

Then I solved the equation  . Two of the solutions are x = a and x = b as I expected. (This means that you could do synthetic division by hand since you know two of the roots.) The other two I did not expect. They are:

. Two of the solutions are x = a and x = b as I expected. (This means that you could do synthetic division by hand since you know two of the roots.) The other two I did not expect. They are:

and

and

And that’s when I stopped astonished! Those numbers are the Golden Ratio  , and its reciprocal

, and its reciprocal  . So the roots are

. So the roots are  and

and  . How did they get there?

. How did they get there?

To this day I have no idea why the Golden Ratio should be so involved with quartic polynomials, but there they are in every quartic!

There were no assumptions made about a and b – they could be Complex numbers. In that case there are no points of inflection, but the “line” and the quartic still will have the same value at the four points.

October 16, 2022 Update: If the solutions of  are the Complex conjugates

are the Complex conjugates  and

and  then

then  and

and  . When graphed on an Argand diagram the four points are collinear on the vertical line at

. When graphed on an Argand diagram the four points are collinear on the vertical line at

This was all in 2013 and until just this year I never checked the ratio of the areas. (They check.)

Here is a CAS printout of the entire computation.

An interactive Desmos demo of this can be found here

October 16, 2022, Update: If the solutions of  are the Complex conjugates

are the Complex conjugates  and

and  then

then  and

and  . When graphed on an Argand diagram the four points are collinear on the vertical line at

. When graphed on an Argand diagram the four points are collinear on the vertical line at

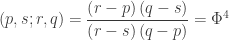

November 10, 2020, Update: I received an email this week form Dominique Laurain, a computer science and applied math engineer from France, who describes himself as a mathematics hobbyist. He discovered another interesting relationship between the coordinates of the x-coordinates of the four points on the line described above. The four points on the line through the points of inflection of a fourth degree polynomial with Real roots in the drawing above from left to right are p, q, r, and s. The coordinates of the points of inflection are a and b as in the post above.

One, of several, cross-ratios of four points with x-coordinates of p, q r, and s is defined as

.

.

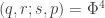

Dominique Laurin discovered that

The computation is shown in the figure below.

There are 24 other cross-ratios depending on the order of the points. In groups of 4, the 24 possible orders are equal to 6 related values. See the cross-ratio link above above. For example, the cross-ratio in the order (s, p; r, q) is

Also,

Also,

Other interesting information:

The Golden Ratio also appears in cubic equations. See the Tashappat – McMullin theorem here.

“Quartic Polynomials and the Golden Ratio” by Harald Totland of the Royal Norwegian Naval Academy. (June 2009)

Speaking of the Golden Ratio, the Calculus Humor website has a nice feature on the Golden Ratio in logos. To view it click here.

Link for cross-ratios

Revised and updated July 20 and 23, 2017, November 10, 2020

and,

then the tradition formula gives

, and

, that bothers me. Where did the

come from?

is the same as multiplying by

is a function of t you must begin by differentiating the first derivative with respect to t. Then treating this as a typical Chain Rule situation and multiplying by

gives the second derivative. (There is a technical requirement here that given

, then

exists.)

and

, and

and

.