Any topic in the Course and Exam Description may be the subject of a free-response question. The two topics listed here have been the subject of full free-response questions or major parts of them.

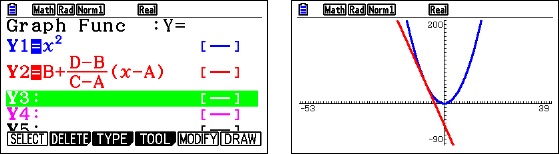

Implicitly defined relations and implicit differentiation

These questions may ask students to find the first or second derivative of an implicitly defined relation. Often the derivative is given and students are required to show that it is correct. (This is because without the correct derivative the rest of the question cannot be done.) The follow-up is to answer questions about the function such as finding an extreme value, second derivative test, or find where the tangent is horizontal or vertical.

What students should know how to do

- Know how to find the first derivative of an implicit relation using the product rule, quotient rule, the chain rule, etc.

- Know how to find the second derivative, including substituting for the first derivative.

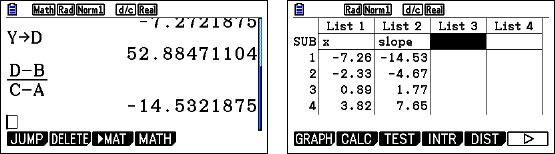

- Know how to evaluate the first and second derivative by substituting both coordinates of a given point. (Note: If all that is needed is the numerical value of the derivative then the substitution is often easier if done before solving for dy/dx or d2y/dx2 and as usual the arithmetic need not be done.)

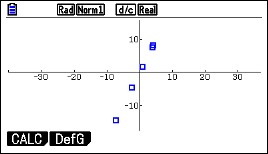

- Analyze the derivative to determine where the relation has horizontal and/or vertical tangents.

- Write and work with lines tangent to the relation.

- Find extreme values. It may also be necessary to show that the point where the derivative is zero is actually on the graph and to justify the answer.

Simpler questions about implicit differentiation my appear on the multiple-choice sections of the exam.

Related Rates

Derivatives are rates and when more than one variable is changing over time the relationships among the rates can be found by differentiating with respect to time. The time variable may not appear in the equations. These questions appear occasionally on the free-response sections; if not there, then a simpler version may appear in the multiple-choice sections. In the free-response sections they may be an entire problem, but more often appear as one or two parts of a longer question.

What students should know how to do

- Set up and solve related rate problems.

- Be familiar with the standard type of related rate situations, but also be able to adapt to different contexts.

- Know how to differentiate with respect to time, that is find dy/dt even if there is no time variable in the given equations. using any of the differentiation techniques.

- Interpret the answer in the context of the problem.

- Unit analysis.

Shorter questions on both these concepts appear in the multiple-choice sections. As always, look over as many questions of this kind from past exams as you can find.

For some previous posts on related rate see October 8, and 10, 2012 and for implicit relations see November 14, 2012

Next Posts:

Friday March 31: For BC Polar Equations (Type 9)

Tuesday April 4: For BC Sequences and Series.

Friday April 7, 2017 The Domain of the solution of a differential equation.