The next few posts will discuss a way to introduce Taylor and Maclaurin series to students. We will kind of sneak up on the idea without mentioning where we are going or using any special terms. In this post we will find a way of approximating a function with a polynomial of any degree we choose. In the next post we will look at the graph of these polynomials and finally suggest some questions for further thought.

Making Better Approximations

Students already know and have been working with the tangent line approximation of a function at a point (a, f(a)):

ln(x):

For the function at the point (1, 0) ask your students to write the tangent line approximation:

.Point out that this line has the same value as ln(x) and its derivative as at (1, 0).

Then suggest that maybe having a polynomial that has the same value, first derivative and second derivative might be a better approximation. Suggest they start with and see if they can find values of a, b and c that will make this happen.

Since we can write

Then suggest they try a third degree polynomial starting with . Proceeding as above, all the numbers come out the same and we find that

Then go for a fourth- and fifth-degree polynomial until they discover the patterns. (The signs alternate, and the denominators are the factorial of the exponent.)

See if the class can write a general polynomial of degree N :

sin(x):

Then have the class repeat all this for a new function such as at the point (0, 0). This could be assigned as homework or group work. Ask them to do enough terms until they see the pattern. There will be patterns similar to ln(x ) and every other term (the even powers) will have a coefficient of zero.

or in general the polynomial of degree N is

How good is this approximation? Using only the first three terms of the polynomial above you will tell you that. Pretty close: correct to 5 decimal places. Using four terms gives correct to 7 decimal places when rounded.

Finally, see if they can generalize this idea to any function f at any point on the function . This time you will not have the various derivatives as numbers, rather they will be expressions like . Work through the powers one at a time to go from

and so on, until you get to

For example the third derivative computation would look like this:

The computations here are perhaps a little different than what students have seen, so take your time doing this. Two or even three class days may be necessary.

Notice these things:

- The first two terms are the tangent line approximation.

- The various derivatives are numbers that must be calculated.

- All the terms of any degree are the same as the terms of the previous degree with one additional term.

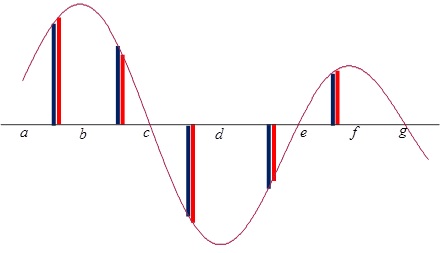

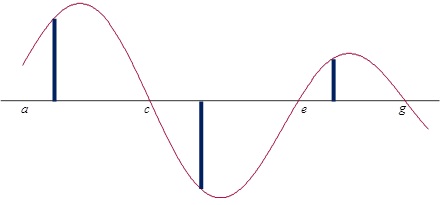

Next post in this series: Looking at all this graphically.

(Typos in an earlier version of this post have been corrected – LMc)