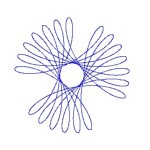

When I first started getting interested in roulettes I began in polar form graphing limaçons. Without going into as much detail as with the roulettes, I offer just one today.

I found this Winplot illustration instructive as to how polar graphs are formed and just how the graphs work and relate to rectangular form graphs of the same functions. So this could be used as a first example, or an investigation of its own.

For my example we will consider the limaçon, or a cardioid with an inner loop, given below (using t for the usual theta, since the LaTex translator doesn’t seem to be able to handle thetas).

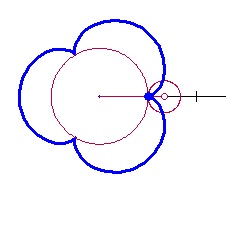

In polar form is a circle with center at the pole and radius of 1.4.This is shown in light blue in the figures.

The polar curve is a circle with center at

and radius of 1. This is shown in orange in the figures below.

The graph in the example is the directed distance (length of the vector) from

to

and is shown by the green arrow in figures 1, 3, and 4.

The blue arrow is congruent to the green with its tail at the pole; its point traces the limaçon shown in black. (Click to enlarge.)

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- In figure 1, the distance is positive and both arrows point in the same direction along the rotating ray.

- In figure 2, the two circles intersect and the distance between them is zero. The limaçon goes through the origin.

- In figure 3, the curves have changed position and the directed distance is negative. The blue arrow points in the negative direction opposite to the rotating ray drawing the inner loop.

- In figure 4, the arrows return to pointing in the same direction, but are longer due to the fact that the distance runs from the orange circle to the far side of the light blue circle forming the bottom outside loop

In the clip below the limaçon is drawn as the black ray rotates from 0 to radians. Watch how the green and blue arrows (always the same length, but not the same direction), work to draw the limaçon.

On the right side of the clip are the two functions graphed in rectangular form. The blue arrow on the right is the same length as the blue arrow on the left and gives the directed distance from to

. This form is probably more familiar to students and may help them see the relationships.

This form is probably more familiar to students and may help them see the relationships. The Winplot file may be downloaded here. If you or your students what to investigate further, click on the Winplot graph and then CTRL+SHIFT+N to see the notes; they will also tell you how to change the A, B, and R sliders to change the curves.