Let’s end the year with this problem that I came across a while ago in a review book:

Integrate

It was a multiple-choice question and had four choices for the answer. The author intended it to be done with a u-substitution but being a bit rusty I tried integration by parts. I got the correct answer, but it was not among the choices. So I thought it would make a good challenge to work on over the holidays.

-

- Find the antiderivative using a u-substitution.

- Find the antiderivative using integration by parts.

- Find the antiderivative using a different u-substitution.

- Find the antiderivative by adding zero in a convenient form.

Your answers for 1, 3, and 4 should be the same, but look different from your answer to 2. The difference is NOT due to the constant of integration which is the same for all four answers. Show that the two forms are the same by

- “Simplifying” your answer to 2 and get a third form of the answer.

- “Simplifying” your answer to 1, 3, 4 and get that third form again.

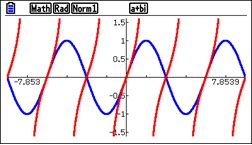

Give it a try before reading on. The solutions are below the picture.

Method 1: u-substitution

Integrate

Method 2: By Parts

Integrate

Method 3: A different u-substitution

Integrate

This gives the same answer as Method 1.

Method 4: Add zero in a convenient form.

Integrate

This, also, gives the same answer as Methods 1 and 3.

So, by a vote of three to one Method 2 must be wrong. Yes, no, maybe?

No, all four answers are the same. Often when you get two forms for the same antiderivative, the problem is with the constant of integration. That is not the case here. We can show that the answers are the same by factoring out a common factor of . (Factoring the term with the lowest fractional exponent often is the key to simplifying expressions of this kind.)

Simplify the answer for Method 2:

Simplify the answer for Methods 1, 3, and 4:

So, same answer and same constant.

Is this a good question? No and yes.

As a multiple-choice question, no, this is not a good question. It is reasonable that a student may use the method of integration by parts. His or her answer is not among the choices, but they have done nothing wrong. Obviously, you cannot include both answers, since then there will be two correct choices. Moral: writing a multiple-choice question is not as simple as it seems.

From another point of view, yes, this is a good question, but not for multiple-choice. You can use it in your class to widen your students’ perspective. Give the class a hint on where to start. Even better, ask the class to suggest methods; if necessary, suggest methods until you have all four (… maybe there is even a fifth). Assign one-quarter of your class to do the problem by each method. Then have them compare their results. Finally, have them do the simplification to show that the answers are the same.

My next post will be after the holidays.

Happy Holidays to Everyone!

.