A know a lot of people like mathematics because there is only one answer, everything is exact. Alas, that’s not really the case. Numbers written as non-terminating decimals are not “exact;” they must be rounded or truncated somewhere. Even things like and 5/17 may look “exact,” but if you ever had to measure something to those values, you’re back to using decimal approximations.

There are many situations in mathematics where it is necessary to find and use approximations. Two if these that are usually considered in introductory calculus courses are approximating the value of a definite integral using the Trapezoidal Rule and Simpson’s Rule and approximating the value of a function using a Taylor or Maclaurin polynomial.

If you are using an approximation, you need and want to know how good it is; how much it differs from the actual (exact) value. Any good approximation technique comes with a way to do that. The Trapezoidal Rule and Simpson’s Rule both come with expressions for determining how close to the actual value they are. (Trapezoidal approximations, as opposed to the Trapezoidal Rule and Simpson’s Rule per se, are tested on the AP Calculus Exams. The error is not tested.) The error approximation using a Taylor or Maclaurin polynomial is tested on the exams.

The error is defined as the absolute value of the difference between the approximated value and the exact value. Since, if you know the exact value, there is no reason to approximate, finding the exact error is not practical. (And if you could find the exact error, you could use it to find the exact value.) What you can determine is a bound on the error; a way to say that the approximation is at most this far from the actual value. The BC Calculus exams test two ways of doing this, the Alternating Series Error Bound (ASEB) and the Lagrange Error Bound (LEB). These two techniques are discussed in my previous post, Error Bounds. The expressions used below are discussed there.

Examining Some Error Bounds

We will look at an example and the various ways of computing an error bound. The example, which seems to come up this time every year, is to use the third-degree Maclaurin polynomial for sin(x) to approximate sin(0.1).

Using technology to twelve decimal places sin(0.1) = 0.099833416647

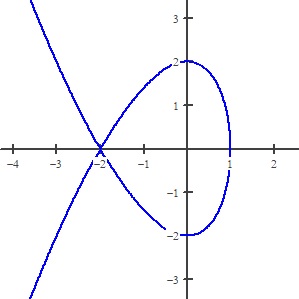

The Maclaurin (2n – 1)th-degree polynomial for sin(x) is

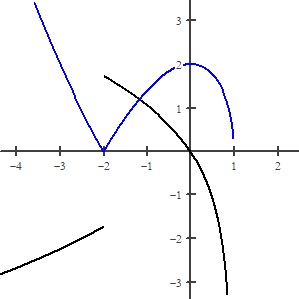

So, using the third degree polynomial the approximation is

The error to 12 decimal places is the difference between the approximation and the 12 place value. The error is:

Using the Alternating Series Error Bound:

Since the series meets the hypotheses for the ASEB (alternating, decreasing in absolute value, and the limit of the nth term is zero), the error is less than the first omitted term. Here that is

The actual error is less than B1 as promised.

Using the Legrange Error Bound:

For the Lagrange Error Bound we must make a few choices. Nevertheless, each choice gives an error bound larger than the actual error, as it should.

For the third-degree Maclaurin polynomial, the LEB is given by

for some number z between 0 and 0.1.

The fourth derivative of sin(x) is sin(x) and its maximum absolute value between 0 and 0.1 is |sin(0.1)|. So, the error bound is

However, since we’re approximating sin(0.1) we really shouldn’t use it. In a different example, we probably won’t know it.

What to do?

The answer is to replace it with something larger. One choice is to use 0.1 since 0.1 > sin(0.1). This gives

The usual choice for sine and cosine situations is to replace the maximum of the derivative factor with 1 which is the largest value of the sine or cosine.

Since the 4th degree term is zero, the third-degree Maclaurin Polynomial is equal to the fourth-degree Maclaurin Polynomial. Therefore, we may use the fifth derivative in the error bound expression, to calculate the error bound. The 5th derivative of the sin(x) is cos(x) and its maximum value in the range is cos(0) =1.

for some number z between 0 and 0.1.

I could go on ….

Since B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5 are all greater than the error, which should we use? Or should we use something else? Which is the “best”?

The error is what the error is. Fooling around with the error bound won’t change that. The error bound only assures you your approximation is, or is not, good enough for what you need it for. If you need more accuracy, you must use more terms, not fiddle with the error bound.