First in a series.

I am going to (try to) write a series of posts this fall on graphing calculator use in for calculus. Graphing calculators became generally available around 1989 and were made a requirement for use on the AP calculus exams in 1995. The hope was that they would encourage the use of technology generally in all math classes, and to an extent this has happened. In the coming posts I hope to show how graphing calculators can be used beyond the four skills required for the AP exams to help students understand what’s going on.

I will occasionally work with CAS calculators, but the main focus will be the basic non-CAS graphing calculators. All the suggestions will work of CAS calculators, of course. Also, I will occasionally make use of Desmos a free online graphing utility that students can easily access on their computer, tablet or smart phone.

Today I will discuss the four things students should be able to do, and in fact are required to do, on the AP exams. I will also show how to store and recall numbers. This last skill, while not required, is very useful. I have found that some teachers, and therefore their students, are unaware of this common feature of graphing calculators.

Calculators and other technology should be available from at least Algebra 1 on. So by the time students get to calculus calculator use (except for the calculus specific operations) should all be second nature to them.

So let’s get going. Here are the four required skills and some brief comments on each.

- Graph a function in a suitable window. The exam questions do not say “use a calculator”, so students are expected to know when seeing a graph will help them. The viewing window is not usually specified either so students should be familiar with setting the viewing window. If the domain is given in the question, then that’s what the students should use. If no domain is given, then use a range that includes the answer choices.

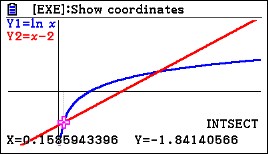

- Solve an equation numerically. Students may use any built-in feature to do this. The home screen “solver”, a routine called “Poly” or “Poly solve” are all allowed. Probably the most useful is to graph both sides of the equation and then use the graph operation called “intersect” to find the points of intersection one at a time. Another approach is to set the equation equal to 0, graph that expression and use the “roots” or “zeros” operations to solve the equation.

- Find the value of the derivative of a function at a given point. There is a built-in template for this.

- Find the value of a definite integral. There is a built-in template for this also.

Store-and-Recall

I will demonstrate the store-and-recall idea with an example that will also use skill 1, 2, and 4 from the list above.

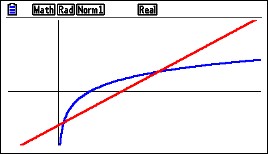

Example: Find the area between the graph of f(x) = ln(x) and g(x) = x – 2, using (1) vertical rectangles, and (2) using horizontal rectangles.

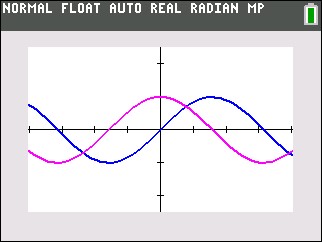

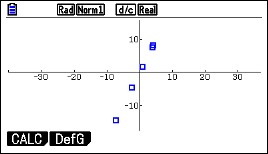

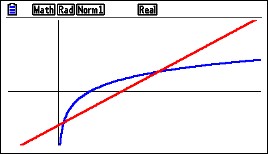

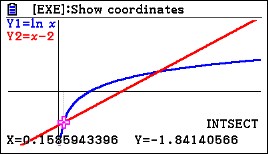

For either method we need the coordinates of the points of intersection of the graphs. So, begin by graphing the functions and adjusting the window so the important points are visible.

Next use the intersection operation to find the first point of intersection.

Next use the intersection operation to find the first point of intersection.

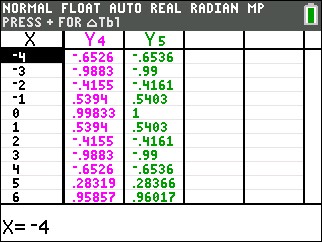

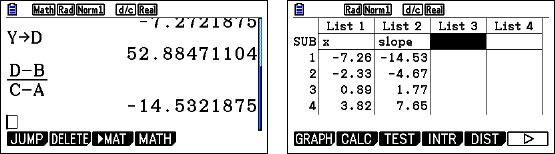

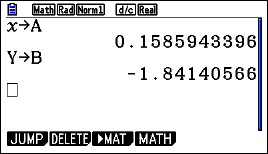

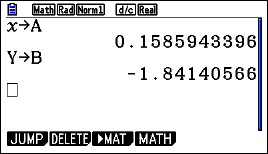

Different calculators will do this slightly differently. The coordinates of the points of intersection are shown at the bottom of the screen. Think of this point as (a, b). The coordinates need to be stored for use later. To do this return to the home screen and type

[x] [STO], [alpha] [A] and [alpha] [y] [STO] [alpha] [B]

If your graph screen shows different names, such as xc and yc, then type that befroe the [STO] key. (The store [STO] key may look like an arrow pointing right.)

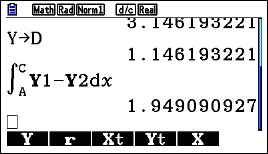

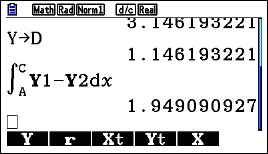

Return to the graph screen and find the coordinates of the second point of intersection; think of this as (c, d). Return to the home screen and store the coordinates as C and D. They are c = 3.146193221 and d = 1.146193221.

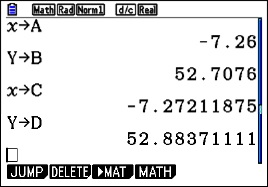

To find the area use the definite integral template and enter the information needed. For the vertical rectangles you may use either the function or Y1 and Y2 that you entered to graph.

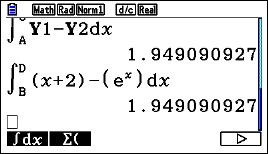

Notice that the upper and lower limits of integration are A and C. The calculator uses the values you stored in these locations. You can use the variables in any kind of computation.

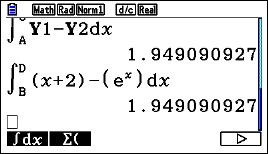

Here is the horizontal rectangle computation using B and D as limits. The functions solved for y are x = y + 2 on the right and x = ey on the left. (The y’s have been changed to x’s since the template only allows x as a variable.)

Notice that so far, we’ve written nothing down. Everything has been done on the calculator. This prevents copy errors and round-off errors.

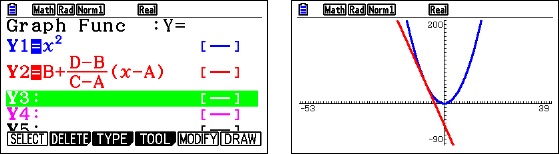

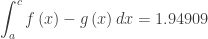

What should a student show on his or her AP Exam? They are required to show what they are doing, or more precisely what they’ve asked their calculator to do. They need to write the equation they are solving with the solution next to it, but no intermediate work. They should indicate what A and C are. So

Then show the integral and answer. Here again they may use f and g given in the stem or the actual expressions. There is no requirement that answers must be given to three decimal places, so there is no need to round.

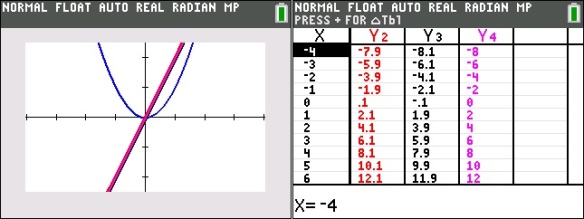

The next post in this series will show you a way to introduce the idea odf the derivative as the slope of the tangent line.

, and