The Rule of Four suggests that mathematics be studied from the analytical, graphical, numerical, and verbal points of view. Proof can only be done analytically – using symbols and equations. Graphs, numbers, and words aid in that, but do not by themselves prove anything.

On the other hand, numbers and especially graphs can make many of the theorems much more understandable and often can convince one of the truth of a theorem far better than the actual proof.

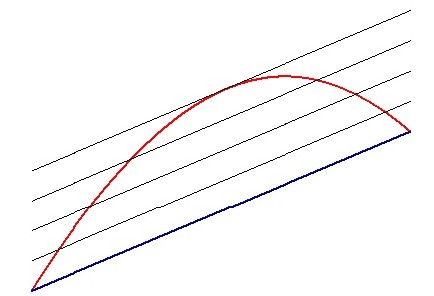

The Mean Value Theorem, MVT, is a good example; it can be demonstrated with a lot less trouble. See the figure above. Picture the blue line connecting the endpoints of the interval (the secant line) moving up, parallel to its original position. See the figure above. As this line moves up it intersects the graph twice, until eventually, just before it does not intersect at all, it comes to a place where it intersects exactly one. At this point it is tangent to the original graph. Since it is tangent, the slope of the line is the same as the derivative,  , at that point.

, at that point.

So, the derivative is equal to the slope of the line between the endpoints. The MVT says that if its hypotheses are true, then there must be a place where the slope of the tangent line is parallel to the slope of the secant line.

But wait, there is more: at that point the instantaneous rate of change of the function is equal to the average rate of change over the interval.

This shows a real strength of looking at the graph.

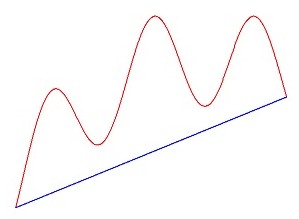

But it is only one of many possible graphs. The graph could look like this figure:

Here there are several places (5 to be exact) where the tangent line is parallel to the secant line; there could be several on one side, or several on both sides. But this is not a problem; this does not contradict the MVT, which says there is at least one.

Yet another way to show the MVT is this. Near the left end of the first graph above the slope of the tangent to the graph (the derivative) is larger than the slope of the secant line; near the right end the slope of the tangent is less than the slope of the secant. So somewhere in between, by the Intermediate Value Theorem, the slope of the tangent must equal the slope of the secant. (For the purists out there, this is from Darboux’s theorem, and requires a slightly stronger hypothesis, namely that the one-sided derivatives at a and b exist.)

Rolle’s theorem can be demonstrated with either of these approaches as well. Rolle’s Theorem is really a special case of the MVT where the slope of the secant line is zero.

In conclusion, I think that this sequence of theorems is a good place to do a little proving of theorems. On the other hand you can easily show the results other ways. In fact, the method at the beginning of this post should be shown anyway in order to give students a good picture (no pun intended) of the MVT. It will help them remember what it is all about.