What does an asymptote of the derivative tell you about the function? How do asymptotes of a function appear in the graph of the derivative?

One of my most read posts is Reading the Derivative’s Graph, first published seven years ago. The long title is “Here’s the graph of the derivative; tell me about the function.” It tells how to quickly find information about the graph of a function from the derivative’s graph. I received a question from a reader recently that asked about asymptotes and the derivative, a topic that I did not cover in that post. So, I tried to find the relationship. The short answer is that an asymptote of the derivatives does not tell you much about the graph of the function. (This is probably why the idea has never been tested on the AP Calculus Exams.)

Nevertheless, there is some calculus to be learned here. You may be able to find some questions for your students to investigate on this topic. Here’s what i determined.

Before we start, here are two terms that are useful, but not commonly used.

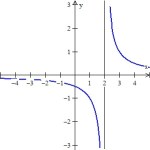

- An even vertical asymptote is one for which the function increases or decreases without limit on both sides of the asymptote. In other words, as x approaches a the function approaches infinity or negative infinity from both sides. The function

has an even vertical asymptote at x = 2. (Figure 1)

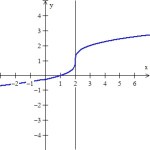

- An odd vertical asymptote is one for which the function increases without bound on one side and decreases without bound on the other. The function

has an odd vertical asymptote at x = 2. (Figure 2) Likewise, the tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant functions have odd vertical asymptotes.

- Figure 1: An EVEN vertical asymptote

- Figure 2: An ODD vertical asymptote

If a function has an odd vertical asymptote, then its derivative will have an even vertical asymptote. (Ask your students to explain why.)

If a function has an even vertical asymptote, then its derivative will have an odd vertical asymptote. (Ask your students to explain why.)

The converses of these two statements are false. That is, a vertical asymptote of the derivative does not necessarily indicate an asymptote of the function. The catch is continuity.

Continuous Functions

If the derivative exists at x = a, then the function is continuous there. But, since we are considering asymptotes of the derivative, we cannot know from the derivative alone if the function is continuous where the derivative has an asymptote.

A simple cusp is a situation in which at an extreme point the graph is tangent to a vertical line. See Figure 3. (Or, you could say, the tangent lines from each side are coincident. Here we will limit the discussion to a vertical tangent line.) A continuous function that has a cusp will show an odd vertical asymptote on its derivative’s graph.

An example is that has a cusp at the point (2,1). (Figure 3).

A continuous function that has a vertical tangent line not a cusp, has an even vertical asymptote on its derivative’s graph. For example, at (2,0) (Figure 4).

- Figure 3: A cusp at (2,1)

- Figure 4: A vertical tangent line.

If you are given the graph of the derivative and it shows a vertical asymptote at x = a, and you know the function is continuous there, then

- an odd vertical asymptote of the derivative indicates cusp on the graph of the function. This will also be an extreme value. (Ask your students to explain why.)

- an even vertical asymptote of the derivative indicates vertical tangent line on the graph of the function, but not an extreme value. (Ask your students to explain why.)

Other than these, there is no easy way to tell what situation produced an asymptote on the derivative.

Functions that are not continuous

If the function is not continuous at x = a, then things get a lot more complicated.

- If the function is not continuous at x = a, then an even vertical asymptote of the derivative may indicate an odd vertical asymptote on the graph of the function. There is no way to be sure.

- If the function is not continuous at x = a, then an odd vertical asymptote of the derivative may indicate an even vertical asymptote on the graph of the function. There is no way to be sure.

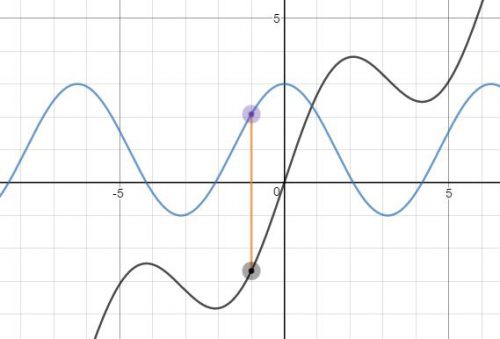

Consider this function:

See Figure 5. The function is defined for all Real numbers and has a jump discontinuity at x = 2. The derivative has an odd vertical asymptote there: and

. Compare this with h(x) above.

- Figure 5

In fact,. Go figure.

For considerations of horizontal asymptotes and the derivative see Other Asymptotes