Another of my favorite questions from past AP exams is from 2000 question AB 4. If memory serves it is the first of what became known as an “In-out” question. An “In-out” question has two rates that are working in opposite ways, one filling a tank and the other draining it.

Another of my favorite questions from past AP exams is from 2000 question AB 4. If memory serves it is the first of what became known as an “In-out” question. An “In-out” question has two rates that are working in opposite ways, one filling a tank and the other draining it.

In subsequent years we saw a question with people entering and leaving an amusement park (2002 AB2/BC2), sand moving on and off a beach (2005 AB 2), another tank (2007 AB2), an oil leak being cleaned up (2008 AB 3), snow falling and being plowed (2010 AB 1), gravel being processed (2013 AB1/BC1), and most recently water again flowing in and out of a pipe (2015 AB1/BC1). The in-between years saw rates in one direction only but featured many of the same concepts.

The questions give rates and ask about how the quantity is changing. As such, they may be approached as differential equation initial value problems, but there is an easier way. This easier way is that a differential equation that gives the derivative as a function of a single variable, t, with an initial point always has a solution of the form

.

This is sometimes called the “accumulation equation.” The integral of a rate of change gives the net amount of change over the interval of integration

. When this is added to the initial amount the result is an expression that gives the amount at any time t.

In a motion context, this same idea is that the position at any time t, is the initial position plus the displacement:

where

The scoring standard gave both forms of the solution. The ease of the accumulation form over the differential equation solution was evident and subsequent standards only showed this one.

2000 AB 4

The question concerned a tank that initially contained 30 gallons of water. We are told that water is being pumped into the tank at a constant rate of 8 gallons per minute and the water is leaking out at the rate of gallons per minute.

Part a asked students to compute the amount of water that leaked out in the first three minutes. There were two solutions given. The second solves the problem as an initial value differential equation:

Let L(t) be the amount that leaks out in t minutes then

since nothing has leaked out yet, so C = -2/3

The first method, using the accumulation idea takes a single line:

I think you’ll agree this is easier and more direct.

Part b asked how much water was in the tank at t = 3 minutes. We have 30 gallons to start plus 8(3) gallons pumped in and 14/3 gallons leaked out gives 30 + 24 – 14/3 = 148/3 gallons.

This part, worth only 1 point, was a sort of hint for the next part of the question.

Part c asked students to write an expression for the total number of gallons in the tank at time t.

Following part b the accumulation approach gives either

or

.

The first form is not a simplification of the second, but rather the second form is treating the difference of the two rates, in minus out, as the rate to be integrated.

The differential equation approach is much longer and looks like this:

, so

Again, this is much longer. In recent years when asking student to write an expression such as this, the directions included a phrase such as “write an equation involving one or more integrals that gives ….” This pretty much leads students away from the longer differential equation initial value problem approach.

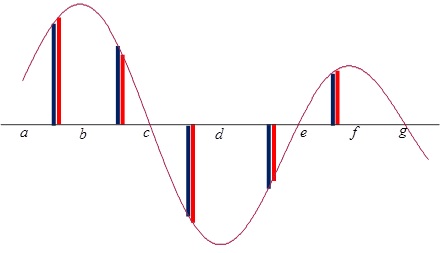

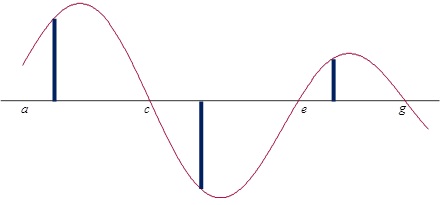

Part d required students to find the time when in the interval minutes the amount of water in the tank was a maximum and to justify their answer. The usual method is to find the derivative of the amount, A(t), set it equal to zero, and then solve for the time.

Notice that this is the same regardless of which of the three forms of the expression for A(t) you start with. Thus, an excellent example of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus used to find the derivative of a function defined by an integral. Or you could just start here without reference to the forms above: the overall rate in the rate in minus the rate out.

when t = 63

This is a maximum by the First Derivative Test since for 0 < t < 63 the derivative of A is positive and for 63 < t <120 the derivative of A is negative.

There is an additional idea on this part of the question in the Teaching Suggestions below.

I like this question because it is a nice real (as real as you can hope for on an exam) situation and for the way the students are led through the problem. I also like the way it can be used to compare the two methods of solution. Then the way they both lead to the same derivative in part d is nice as well. I use this one a lot when working with teachers in workshops and summer institutes for these very reasons.

Teaching Suggestions

- Certainly, have your students work through the problem using both methods. They need to learn how to solve an initial value problem (IVP) and this is good practice. Additionally, it may help them see how and when to use one method or the other.

- Be sure the students understand why the three forms of A(t) in part c give the same derivative in part d. This makes an important connection with the Fundamental theorem of Calculus.

- Like many good AP questions part d can be answered without reference to the other parts. The question starts with more water being pumped in than leaking out. This will continue until the rate at which the water leaks out overtakes the rate at which it is being pumped in. At that instant the rate “in” equals the rate “out” so you could start with

. After finding that t = 63, the answer may be justified by stating that before this time more water is being pumped in than is leaking out and after this time the rate at which water leaks out is greater than the rate at which it is pumped in, so the maximum must occur at t = 63.

- And as always, consider the graph of the rates.

I used this question as the basis of a lesson in the current AP Calculus Curriculum Module entitled Integration, Problem Solving and Multiple Representations © 2013 by the College Board. The lesson gives a Socratic type approach to this question with a number of questions for each part intended to help the teacher not only work through this problem but to bring out related ideas and concepts that are not in the basic question. The module is currently available at AP sponsored workshops and AP Summer Institutes. Eventually, it will be posted at AP Central on the AB and BC Calculus Home Pages.