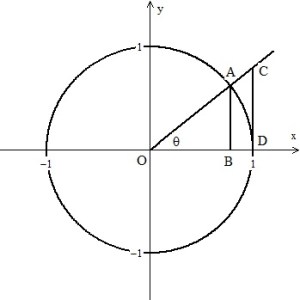

About this time every year the AP Calculus Community discussion turns to the sentence, “A function is continuous on its domain.” Functions such as cause confusion – is it continuous or not? The confusion comes, I think, from the way we introduce continuity to new calculus students.

We say – and I did say this myself just last week – that the graph of a continuous function can be drawn without taking your pencil off the paper. That idea helps students get a start on understanding what continuity means, but it is not quite correct.

The definition of continuity requires that for a function to be continuous at a point, the limit at that point equals the value there (and that both the limit and value be finite). The only way a function can have a value at a point is if the point is in the domain. So, the definition of continuity can be applied only at points in the domain. If the domain of the function is not all Real numbers, then the function cannot be continuous “everywhere;” rather it can only be continuous on its domain. (And, of course, there are many examples of functions that are not continuous at all points in their domains.)

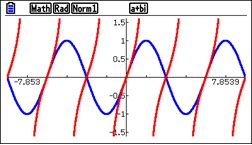

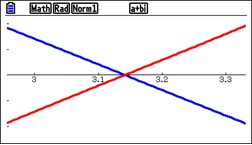

So what do you say about a function like ?

Its domain is all Real numbers . The function is continuous at all the points in its domain and so it is continuous on its domain.

But that statement does not tell the whole story. We asked the wrong question. We should ask where the function is not continuous. If we ask where this function is not continuous, the answer is that the function is not continuous at x = 0. Asking where a function is not continuous requires that we consider the entire number line, all Real numbers. The answer often provides better information.

So then, obviously a function is not continuous at any and all the points not in its domain (plus perhaps some other points in its domain). Accepting that a function is continuous on its domain, even if correct, does give us as much information as asking where a function is not continuous.

Ask the right question!