This is an exploration based on the AP Calculus question 2018 AB 6. I originally posed it for teachers last summer. This will make, I hope, a good review of many of the concepts and techniques students have learned during the year. The exploration, which will take an hour or more, includes these topics:

- Finding the general solution of the differential equation by separating the variables

- Checking the solution by substitution

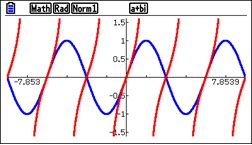

- Using a graphing utility to explore the solutions for all values of the constant of integration, C

- Finding the solutions’ horizontal and vertical asymptotes

- Finding several particular solutions

- Finding the domains of the particular solutions

- Finding the extreme value of all solutions in terms of C

- Finding the second derivative (implicit differentiation)

- Considering concavity

- Investigating a special case or two

I also hope that in working through this exploration students will learn not so much about this particular function, but how to use the tools of algebra, calculus, and technology to fully investigate any function and to find all its foibles.

The exploration is here in a PDF file. Here are the solutions.

As always, I appreciate your feedback and comments. Please share them with me using the reply box below.

The College Board is pleased to offer a new live online event for new and experienced AP Calculus teachers on March 5th at 7:00 PM Eastern.

I will be the presenter.

The topic will be AP Calculus: How to Review for the Exam: In this two-hour online workshop, we will investigate techniques and hints for helping students to prepare for the AP Calculus exams. Additionally, we’ll discuss the 10 type questions that appear on the AP Calculus exams, and what students need know and to be able to do for each. Finally, we’ll examine resources for exam review.

Registration for this event is $30/members and $35/non-members. You can register for the event by following this link: http://eventreg.collegeboard.org/d/xbqbjz