At the school where I am teaching this year, all of the students, K – 12, are issued iPads. Whether this is the coming thing in education or not, I cannot say. I like the idea, but then I like technology in teaching and learning. My school issued iPad is my fourth. I offer today a few observations, anecdotal to be sure, for those who are curious about this growing trend.

First, the school owns the iPads. Therefore, the school restricts what apps students can use on them. The school can see what is on each iPad. Students are able to download apps only from the school’s approved list. The school pays for some of the recommended apps. The iPads do not have Apps Store access. The school owns and uses software to make this possible. Students who manage to get around the system are called in and the problem is corrected.

Websites that are not approved are blocked on the school’s server. Students can still access the entire web away from the school.

Yes, the students have games on their iPads, and yes, they try to play them in class. There is also instant messaging and e-mail. The teachers have to keep an eye on what the kids are doing – nothing new about that.

Many of the teachers require students to do their reports and essays using one of the apps available. Students are getting very good at note talking on their machines. Notability (about $3) seems to be the most popular app for this. Even in math classes students can take their notes and do their homework without benefit of paper. Some students e-mail me their homework on days when I collect it.

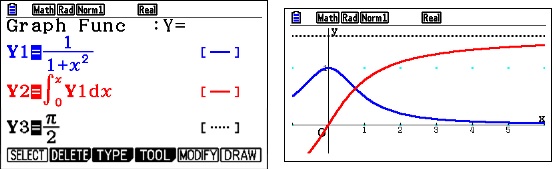

There are a variety of graphing apps available all of which produce far better graphs than graphing calculators. Good Grapher Pro is my favorite and very easy to use for both 2D and 3D graphs.

Graphing by hand is a problem. Note-taking apps have grid backgrounds, but it is difficult to plot points, and draw lines or curves as neatly as you can on paper.

My calculus classes have access to an electronic copy of their textbook online. It is available anywhere there is internet access. They have a full copy of everything in the text and it looks just like the text. Most of the drawings are animated in the online version – this is a big plus. Also, it is easy to copy an individual problem, say a definite integral, and paste it into Notability or another app and work on it.

My Algebra 1 students do not have an online copy available. They do the next best thing. They photograph the homework page and do their problems from the picture.

It turns out that I am not 100% technology: I still give most of my notes and work the homework problems on a whiteboard. Some students photograph what I write. Then they take the picture home and use it to study from – at least that’s what they tell me. I hope this is a help. I can talk and write on the board much faster than students can write. It seems to me that sometimes note taking can be a distraction. That is, kids are so busy writing down everything that they are not following the flow of ideas. So, if listening and then taking a picture helps them learn better, I’m all for it.

I also post assignments, worksheets, and so forth online. Students download them to their iPads and always have them handy.

In a previous post I discussed how I use an app called Socrative in my classes.

Please share your experiences with in-class iPad use. Use the “leave a comment” link below.