Differential Equations 1

The next several posts will cover the fundamentals of the topic of differential equations at least as far as is needed for an AP Calculus course. We will begin at the beginning.

What is a differential equation?

A differential equation is an equation with one or more derivatives in it. It may be very simple such as , or more complicated such as

or even more complicated.

Why do we need differential equations?

It is often not possible to determine directly a regular function that applies to a real situation. However, we may be able to measure how something is changing with respect to time. The change with respect to time is a derivative and gives us a differential equation. Once in college, as you may remember, there are entire courses devoted to using and solving differential equations. Power series (a BC topic) are often used to approximate or find the solution to a differential equation.

What is the solution to a differential equation?

The solution of a differential equation is not a number. For the first equations we will consider the short answer is that a solution is a function that when substituted into the differential equation along with its derivatives produces a true statement (an identity).

As you may suspect differential equations, at least the easy ones, are solved by integrating. Thus the solution of first appears to be

. But we quickly realize that

and also

check when substituted into the given equation. In fact any equation with the form

, where C is any constant will check. Because of this we first define the general solution of a differential equation as a function with one or more constants that satisfies the given differential equation.

In order to evaluate the constant(s) we are often given an initial condition. An initial condition is the value of the solution function for a particular value of the independent variable, in other words, a point on the solution’s graph. Once the constant is evaluated, we have what’s called a particular solution.

So if the solution of contains the point (4, 7), then the particular solution is

. A differential equation with an initial condition is called an initial value problem or an IVP.

How do you solve a differential equation?

There is no one method that will let you solve any differential equation. They are not all as simple as the example above. That’s why entire courses are devoted to solving differential equations. AP Calculus students are expected to know only one of the many methods. (This is because there is only time for the briefest introduction of the topic.) The method is called separation of variables. Not all differential equations can be solved by this method; the second example at the top for example requires a much different approach (that is not tested on the AP calculus exams).

To use the method of separation of variables follow these steps:

(1) by multiplying and dividing rewrite, the equation with the x and dx factors on one side and the y and dy factors on the other side.

(2) Then integrate both sides and

(3) Include a constant of integration.

(4) Use the initial condition to evaluate the constant and

(5) Give the particular solution solved for y.

Example 1: For the very simple example we have been using the work looks like this:

Step 1 Separate the variables:

Steps 2 and 3 Integrate and include the constant of integration. Note that there is a different constant on both sides, but they are immediately combined into one constant that is usually put with the x-terms:

Step 4 Use the initial condition to find C:

Stem 5 Write the solution by solving for y:

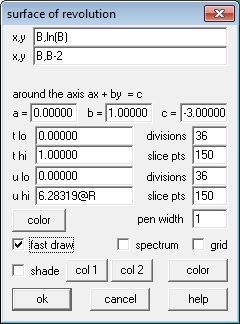

Example 2: An average difficulty question. Find the particular solution of the differential equation such that the point (4, –3) lies on the solution.

Step 1:

Step 2 and 3: or

. Multiplying by 2 to simplify things, The constant in the second form is not the same as in the first. However, it is just another constant so it is okay to call it C again.

Step 4: so

Step 5: and

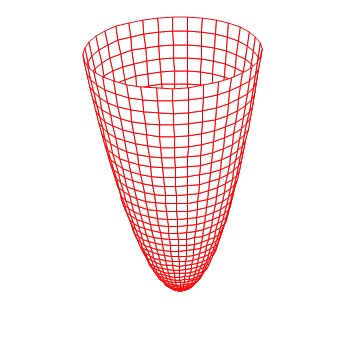

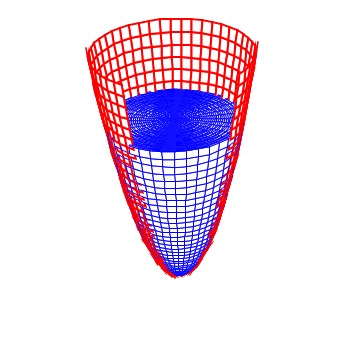

Since the solution must be a function it is necessary to solve for y by taking the square root of both sides. The negative sign is chosen because the initial condition requires a negative value for y. The solution is a semi-circle, the bottom half of the full circle.

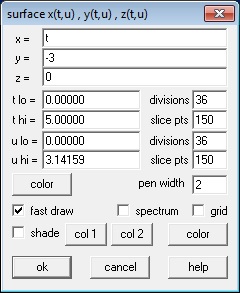

Example 3: A bit more difficult, but the steps are the same. Find the particular solution of the differential equation with the initial condition

. (From the 2008 AB calculus exam question 5c.)

Step 1:

Steps 2 and 3:

Step 4: When x = 2, y =0 so

Step 5: Solve for y:

Raise e to the power on each side to remove the natural logarithm. (Students like to call this “E-ing.”)

Near the initial point (2, 0) , so

, so

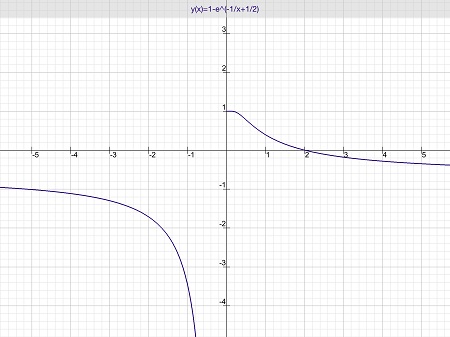

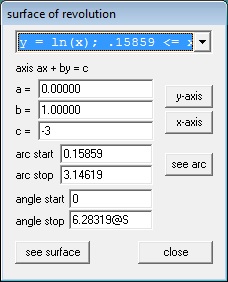

The graph of the solution is the part of the graph shown below for which . See note 2 below:

Two final notes:

- The business with the absolute values is important. Students seem to prefer just ignoring the absolute values, but of course you cannot do that. A similar thing occurred in example 2: since you need the square root of one side you must decide, based on the initial condition, whether to use a plus or a minus sign with the radical. Some practice with both these situations is needed.

- Since

. In order to make this so,

. This is the domain of the solution. Technically, the domain of the particular solution of a differential equation must be an open interval that contains the initial condition, and on which the differential equation is true. Practically, this means that the graph must go through the initial condition point but may not cross an asymptote or contain a point where the function is not defined. The solution in the example is undefined at x = 0. It approaches the y-axis as a vertical asymptote from the left and approaches the point (0,1) from the right. AP students were not required to sort all this out, but a simple graph of the solution will show what’s happening. For more on the domain (which is not really tested) click here.

- For you techies: The graph was made on an iPad using an app called Good Grapher Pro. This is an excellent grapher for 2D and 2D graphs that zoom easily by pinching the screen (of course).