The other day someone asked me a question about the implicit relation . They had been asked to find where the tangent line to this relation is vertical. They began by finding the derivative using implicit differentiation:

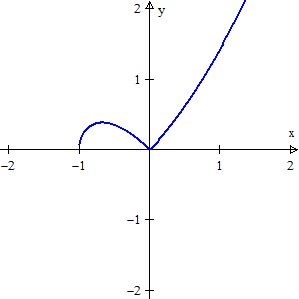

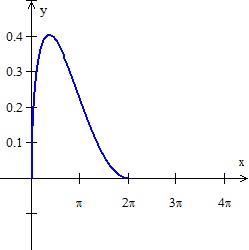

The derivative will be undefined when its denominator is zero. Substituting y = 0 this into the original equation gives . This is true when x = –1 or when x = 0. They reasoned that there will be a vertical tangent when x = –1 (correct) and when x = 0 (not so much). They quite wisely looked at the graph.

The graph appears to run from the first quadrant, through the origin into the third quadrant, up to the second quadrant with a vertical tangent at x = –1, and then through the origin again and down into the fourth quadrant. It looks like a string looped over itself.

What’s going on at the origin? Where is the vertical tangent at the origin?

The short answer is that vertical tangents occur when the denominator of the derivative is zero and the numerator is not zero. When x = 0 and y = 0 the derivative is an indeterminate form 0/0.

In this kind of situation an indeterminate form does not mean that the expression is infinite, rather it means that some other way must be used to find its value. L’Hôpital’s Rule comes to mind, but the expression you get results in another 0/0 form and is no help (try it!).

My thought was to solve for y and see if that helps:

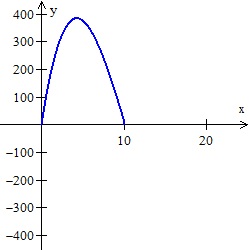

The graph consists of two parts symmetric to the x-axis, in the same way a circle consists of two symmetric parts above and below the x-axis. The figure below shows the top half.

So, the graph does not run from the first quadrant to the third; rather, at the origin it “bounces” up into the second quadrant. The lower half is congruent and is the reflection of this graph in the x-axis.

So, what happens at the origin and why?

The derivative of the top half is . Notice that this is the same as the implicit derivative above. Now a little simplifying; okay a lot of simplifying – who says simplifying isn’t that big a deal?

Now we see what’s happening. As x approaches zero from the right, the derivative approaches +1, and as x approaches zero from the left, the derivative approaches –1. This agrees with the graph. Since the derivative approaches different values from each side, the derivative does not exist at the origin – this is not the same as being infinite. (For the lower half, the signs of the derivative are reversed, due to the opposite sign of the denominator.)

The tangent lines at the origin are x = 1 on the right, and x = –1 on the left, hardly vertical.

What have we learned?

- Indeterminate forms do not necessarily indicate an infinite value. An indeterminate form must be investigated further to see what you can learn about a function, relation, or graph.

- Sometimes simplifying, or at least changing the form of an expression, is helpful and therefore necessary.

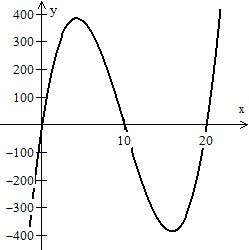

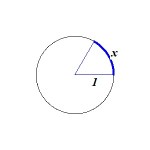

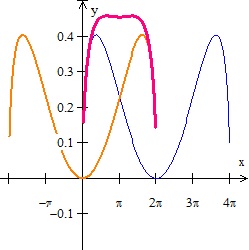

Extension: Using a graphing utility that allows sliders (Winplot, GeoGebra, Desmos, etc) enter and explore the effects of the parameters on the graph.

_________________________

The Man Who Tried to Redeem the World with Logic

WALTER PITTS (1923-1969): Walter Pitts’ life passed from homeless runaway, to MIT neuroscience pioneer, to withdrawn alcoholic. (Estate of Francis Bello / Science Source)

I ran across this article that you might find interesting. It is about Walter Pitts one of the twentieth century’s most important mathematicians we, or at least I, have never heard of. It is from the February 5, 2015 of the science magazine Nautilus