Unit 2 contains topics rates of change, difference quotients, and the definition of the derivative (CED – 2019 p. 51 – 66). These topics account for about 10 – 12% of questions on the AB exam and 4 – 7% of the BC questions.

Topics 2.1 – 2.4: Introducing and Defining the Derivative

Topic 2.1: Average and Instantaneous Rate of Change. The forward difference quotient is used to introduce the idea of rate of change over an interval and its limit as the length of the interval approaches zero is the instantaneous rate of change.

Topic 2.2: Defining the derivative and using derivative notation. The derivative is defined as the limit of the difference quotient from topic 1 and several new notations are introduced. The derivative is the slope of the tangent line at a point on the graph. Explain graphically, numerically, and analytically how the three representations relate to each other and the slope.

Topic 2.3 Estimating the derivative at a point. Using tables and technology to approximate derivatives is used in this topic. The two resources in the sidebar will be helpful here.

Topic 2.4: Differentiability and Continuity. An important theorem is that differentiability implies continuity – everywhere a function is differentiable it is continuous. Its converse is false – a function may be continuous at a point, but not differentiable there. A counterexample is the absolute value function, |x|, at x = 0.

One way that the definition of derivative is tested on recent exams which bothers some students is to ask a limit like

.

.

From the form of the limit students should realize this as the limit definition of the derivative. The h in the definition has been replaced by x. The function is tan(x) at the point where  . The limit is

. The limit is  .

.

Topics 2.5 – 2.10: Differentiation Rules

The remaining topics in this chapter are the rules for calculating derivatives without using the definition. These rules should be memorized as students will be using them constantly. There will be additional rules in Unit 3 (Chain Rule, Implicit differentiation, higher order derivative) and for BC, Unit 9 (parametric and vector equations).

Topic 2.5: The Power Rule

Topic 2.6: Constant, sum, difference, and constant multiple rules

Topic 2.7: Derivatives of the cos(x), sin(x), ex, and ln(x). This is where you use the squeeze theorem.

Topic 2.8. The Product Rule

Topic 2.9: The Quotient Rule

Topic 2.10: Derivative of the other trigonometric functions

The rules can be tested directly by just asking for the derivative or its value at a point for a given function. Or they can be tested by requiring the students to use the rule of an general expression and then find the values from a table, or a graph. See 2019 AB 6(b)

The suggested number of 40 – 50 minute class periods is 13 – 14 for AB and 9 – 10 for BC. This includes time for testing etc. Topics 2.1, 2,2, and 2.3 kind of flow together, but are important enough that you should spend time on them so that students develop a good understanding of what a derivative is. Topics 2.5 thru 2.10 can be developed in 2 -3 days, but then time needs to be spent deciding which rule(s) to use and in practice using them. The sidebar resource in the CED on “Selecting Procedures for Derivative” may be helpful here.

Other post on these topics

DEFINITION OF THE DERIVATIVE

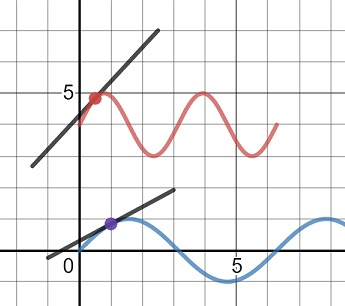

Local Linearity 1 The graphical manifestation of differentiability with pathological examples.

Local Linearity 2 Using local linearity to approximate the tangent line. A calculator exploration.

Discovering the Derivative A graphing calculator exploration

The Derivative 1 Definition of the derivative

The Derivative 2 Calculators and difference quotients

Difference Quotients 1

Difference Quotients II

Tangents and Slopes

Differentiability Implies Continuity

FINDING DERIVATIVES

Why Radians? Don’t do calculus without them

The Derivative Rules 1 Constants, sums and differences, powers.

The Derivative Rules 2 The Product rule

The Derivative Rules 3 The Quotient rule

Here are links to the full list of posts discussing the ten units in the 2019 Course and Exam Description.

2019 CED – Unit 1: Limits and Continuity

2019 CED – Unit 2: Differentiation: Definition and Fundamental Properties.

2019 CED – Unit 3: Differentiation: Composite , Implicit, and Inverse Functions

2019 CED – Unit 4 Contextual Applications of the Derivative Consider teaching Unit 5 before Unit 4

2019 – CED Unit 5 Analytical Applications of Differentiation Consider teaching Unit 5 before Unit 4

2019 – CED Unit 6 Integration and Accumulation of Change

2019 – CED Unit 7 Differential Equations Consider teaching after Unit 8

2019 – CED Unit 8 Applications of Integration Consider teaching after Unit 6, before Unit 7

2019 – CED Unit 9 Parametric Equations, Polar Coordinates, and Vector-Values Functions

2019 CED Unit 10 Infinite Sequences and Series

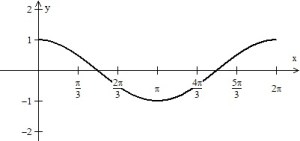

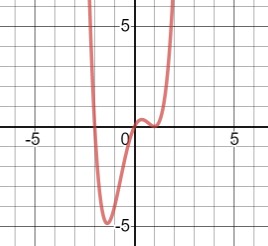

. (See figure 1. A tangent segment at

is drawn.) As you know, this function’s values go smoothly from 0 to 1 to 0 to –1 and back to 0. The slopes of its tangent line, its derivative, appears to go from 1 to 0 to –1 to 0 to 1 as you would expect knowing its derivative is

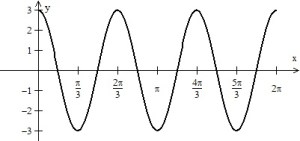

. (See figure 2)

(See figure 3. A tangent line at

is drawn) This takes on all the values of the sine function three times between 0 and

. It goes through the same values three times as fast and therefore, its rate of change (yeah, the derivative) should be three times as much. Compare the tangent lines in Figures 1 and 3. This agrees with the derivative found by the Chain Rule:

. See figure 4)

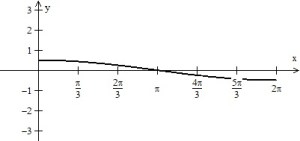

(See figure 5. A tangent line at

is drawn.). This time the function is stretch and only goes through half its period. So, It goes through the same values half as fast as the original and the slope is only half as steep as the original. Compare the tangent lines in Figures 1 and 5.Therefore, the rate of change the derivative, should be only half the original’s. So,

(See figure 6)