In my last post I showed how to use a Desmos graph to discover, by looking at the tangent line as it moved along the graph of the function, the properties of the derivative of a function. This post goes in the opposite direction. Now, instead of discovering the properties of the derivative from the graph of the function, we will use that knowledge to identify important information about the function from the graph of its derivative. We are not discovering anything here; rather we are putting our previous discoveries to use.

One of the uses of the derivative is to deduce properties of its antiderivative, i.e. the function of which it is the derivative. This is an important skill for students to be able to use. It is also a type of question that appears on every Advanced Placement Calculus exam in both the free-response sections and the multiple-choice sections. My previous post on this topic, Reading the Derivative’s Graph, is the most read post on this blog. This post expands on the concepts in that post and shows how to use the Desmos file to help students develop the skills necessary to answer this type of question.

Desmos is free. You and your students can set up their own account and save their own work there. There are also free Desmos apps for tablets and smart phones.

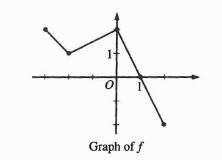

Click on the graph above. Here’s what you should see:

- The first equation on the left side is f(x). This is the function whose antiderivative we will be trying to create. You may change this to any function you wish.

- The second equation is F(x) the antiderivative of f(x). That is F ‘(x) = f(x). Desmos cannot compute an antiderivative so you will need to enter it yourself. Your students need not trust you on this: have them check your equation by differentiating. Of course, at this point they will not be ready to find the analytic form of the antiderivative except for the simplest functions. This comes later in the year.

- Note the “+C” is included and later we will manipulate this with a slider.

- The antiderivative is multiplied by

. This is a way of controlling the “a” slider and should always be multiplied by antiderivative. This is just a syntax trick to make the graph work and is not part of the antiderivative. When x is to the left of a, (x < a) the fraction is 1 and the graph will be seen; when x is to the right of a, (x > a) the expression is undefined, and nothing will graph. As you change “a” with the slider the graph of an antiderivative will be drawn.

- The third equation x = a graphs a dashed vertical to help you line up the corresponding points on the two graphs.

- The next two lines are the “a” and “C” sliders. Make C = 0 for now and move the “a” slider.

At this point students should know things about the relationship between a function and its first and second derivatives. This includes the things they discovered in the previous post such as when the function is increasing the derivative is non-negative, and when the tangent line is above the graph the slope (derivative) is decreasing and the graph of the function is concave down. All of these concepts are really “if, and only if” situations. So we now consider them in reverse and deduce properties of the antiderivative from the properties of the graph of the derivative.

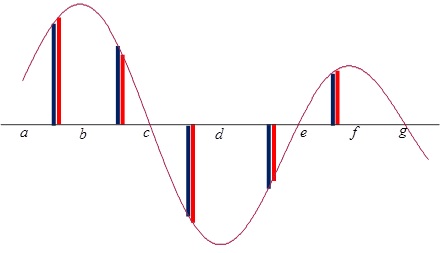

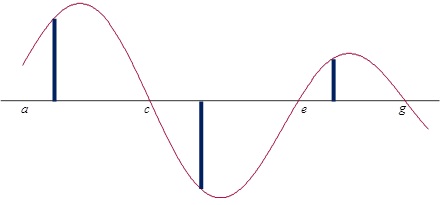

Using the “a” slider starting at the left side of the graph ask the students what the derivative tells them about the function in this part of the domain. Is the function increasing or decreasing? Is it concave up or down? etc. Go slowly from left to right asking what happens next, and why (that is, how do you know? What feature of the derivative tells you this?) This is preparing them to write the justifications required on the AP exams.

Certain points on the graph of the derivative are important. The zeros of the derivative and whether the derivative changes from positive to negative, negative to positive, or neither are important. Likewise, the extreme values of the derivative point to important features of the function – points of inflection.

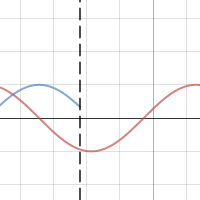

Once you have a complete graph of the antiderivative move the “C” slider.

- Remind students that the derivative of a constant is zero and therefore, the C does not show up in the derivative.

- Discuss is why changing the antiderivative does not change the derivative.

- Ask, how many functions have the same derivative?

- Point out is that by changing “C” the graph of an antiderivative can be made to go through any (every, all) point in the plane.

Switch to a different function and its derivative to reinforce the concepts. Yo will have to enter both the derivative and the antiderivative.Do this as often as necessary. You could also give students or groups of students the graph of a derivative (on paper) and challenge them to sketch the antiderivative.

A disclaimer: A function and its derivative should not be graphed on the same axes, because the two have different units. Nevertheless, I have done it here, and it is commonly done everywhere, to compare the graphs of a function and its derivative so that the important features of the two can be lined up and easily compared.

.