Density, as an application of integration, has snuck onto the exams. It is specifically not mentioned in the “Curriculum Framework” chapter of the 2016 Course and Exam Description, there is one example in the 2020 CED There is an example (#12 p. 58) in the AB sample exam question section of 2020 Course and Exam Description. The first time this topic appeared was in the 2008 AB Calculus exam. There was a hint in the few years before that with a question in the old Course Description book. Both questions will be discussed below. The idea is that students are supposed to understand integration well enough to apply their knowledge to a new situation (density).

The Mathematics

A density function gives the amount of something per unit of length, area, or volume, for example

- The density of a metal rod may be given in units of grams per centimeter.

- The density of the population of a city may be given in units of people per square mile. (See map at end.)

- The density of a container of substance may be given in pounds per cubic foot.

The density can be used to find the amount. In each example, notice that the length, area, or volume of the region is multiplied by the density to find the amount.

Example 1: A 10 cm rod with a constant density of 3 g/cm has a mass of

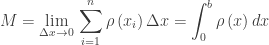

In other situations, the density is not constant and is given by some function. Suppose our metal rod of length b has a density of  grams/cm where x is measured from one end of the rod. To find the total mass we think of cutting the rod in the very small pieces. (Think partition: each piece has a length of

grams/cm where x is measured from one end of the rod. To find the total mass we think of cutting the rod in the very small pieces. (Think partition: each piece has a length of  in which the density is nearly constant say

in which the density is nearly constant say  .) The sum of the mass of these pieces is the Riemann sum

.) The sum of the mass of these pieces is the Riemann sum  . The limit of this expression as

. The limit of this expression as  gives the total mass in grams:

gives the total mass in grams:  Notice that

Notice that  is the length of the rod. This is multiplied by the density to find the mass.

is the length of the rod. This is multiplied by the density to find the mass.

Example 2: The next example is from the old Course Description book.

A city is built around a circular lake that has a radius of 1 mile. The population density of the city is  people per square mile, where r is the distance from the center of the lake, in miles. Which of the following expressions gives the number of people who live within 1 mile of the lake?

people per square mile, where r is the distance from the center of the lake, in miles. Which of the following expressions gives the number of people who live within 1 mile of the lake?

(A)  (B)

(B)

(C)  (D)

(D)

(E)

We need to partition the region so that each piece has a close to a constant density. Thin rings around the lake will accomplish this. A ring, if straightened out is similar to a rectangle of length  where

where  is the distance from the center of the lake (this is the circumference of the ring), the width of this ring (rectangle) is

is the distance from the center of the lake (this is the circumference of the ring), the width of this ring (rectangle) is  . In this ring (rectangle) the population density is people per square mile, so the population in the ring is

. In this ring (rectangle) the population density is people per square mile, so the population in the ring is  approximated by multiplying the area by the density:

approximated by multiplying the area by the density:  . Adding these gives a Riemann sum whose limit gives the total population:

. Adding these gives a Riemann sum whose limit gives the total population:

Answer (D).

Answer (D).

The limits of integration are from the edge of the lake, r = 1 to r = 2 (“one mile from the lake”). Another way to look at this is that  is the area of the city; this is multiplied by the population density to find the population.

is the area of the city; this is multiplied by the population density to find the population.

This type of density situation is called a radial density function.

Notice that the answer looks like the formula for volume by cylindrical shells; this is not quite an accident. The rings around the center are like the shells used when finding volume. It is the units that are different.

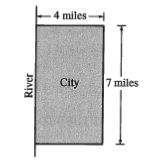

Example 3: From the 2008 AB Calculus exam #92.

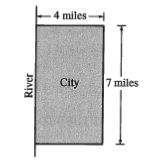

A city located beside a river has a rectangular boundary as shown in the figure above. The population density of the city at any point along a strip x miles from the river’s edge is  people per square mile. Which of the following expressions gives the population of the city?

people per square mile. Which of the following expressions gives the population of the city?

(A)  (B)

(B)  (C)

(C)

(D)  (E)

(E)

A thin vertical strip of the city  miles to the right of the river has an area of

miles to the right of the river has an area of  . The population in each such strip is found by multiplying the area by the density function; this gives

. The population in each such strip is found by multiplying the area by the density function; this gives  . These are then added forming a Riemann sum, etc.

. These are then added forming a Riemann sum, etc.

Answer (B)

Answer (B)

Alternative solution: When I first saw this question, not having thought about density for quite a while, I answered it by doing a unit analysis. Since unit analysis is a good thing for students to understand I’ll outline my thinking next.

We are looking for the population so the answer must be in units of “people.” The density function is in units of “people/square mile” (given). Both x and dx are in units of “miles” and the “7” also has units of “miles.” Therefore, the only choice that gives “people” is the one that multiplies the 7, the dx and the density function. This eliminates (A) and (D). The 28 in (C) must be square miles, making the overall units “people-miles” which is not what we’re going for. Finally, choice (E) is eliminated since the 7 and the dx are not in the same direction. This leaves (B).

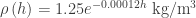

Example 4: A volume problem adapted from Calculus by Hughes-Hallett, Gleason, et al.

The density of air h meters above the earth’s surface is  . Find the mass of a column of air 25 km high with a square base 3 meters on a side sitting on the surface of the earth.

. Find the mass of a column of air 25 km high with a square base 3 meters on a side sitting on the surface of the earth.

At any height, h meters above the earth the volume of a thin slice of the column of air is  . The mass of this slice is

. The mass of this slice is  . The sum of these slices gives a Riemann sum whose limit gives the total volume:

. The sum of these slices gives a Riemann sum whose limit gives the total volume:

For other examples see 2018 BC 2, and 2021 AB 1, Good Question 15 and Good Question 16

Check the index of your textbook for density problems. Calculus by Hughes-Hallett Gleason, et al and Calculus by Rogawski (2nd edition) have good exercises and examples. My advice is not to make too big a deal of this, but if you have time, you can take a look. Should this kind of question appear on the free-response section I would guess that the question will be carefully worded so that students who never saw this kind of question would have a good chance of answering it.

The changing population density of Sydney, Australia in persons per hectare. Note the date changes in the key at the lower left.

Revised and updated 8-20-2019

Coming soon:

- Jan 17th, Every Day series

- Jan 24th, Logistic Growth – Real and Simulated

- Jan 31st, The Logistic Equation

- Feb 7th, Graphing Taylor Polynomials

- Feb 14th, Geometric Series – Far Out