I discovered in doing next week’s post that I apparently never wrote about implicit differentiation. So here goes – an extra post this week!

Implicit Differentiation

The technique of implicit differentiation allows you to find slopes of relations given by equations that are not written as functions or may even be impossible to write as functions.

Example 1: A good way to start investigating this idea is to give your class the equation of a circle, say and ask them to find the slope of the tangent line (the derivative) where x = 3. No hints, just let them try.

Most students will hit upon solving for y and then differentiating:

There are two points where x = 3: (3, 4) and (3, –4) at the first point the slope is – ¾ and at the second ¾.

Then show them another way – implicit differentiation.

To use this technique, assume that y is a function of x, but do not bother to find that function. Then using the chain rule on any terms containing a y. For , we have

Then solve for the derivative

We see that this is the same as we found the first time, since ! There is a slight advantage here: we can now find the slopes from the coordinates without solving or dealing with the plus/minus sign. *

Example 2: Now let’s consider a more difficult example. Find the derivative of . To solve for y here is possible but somewhat difficult (Hint: use the quadratic formula). We can continue writing

for dy/dx.

Note that the last term on the right is differentiated using the product rule. Since this happens fairly often, students need to be reminded of it.

Now solving for gives

Then we can find the derivatives at specific points by substituting the coordinates of the point. At the point (3,2) on the curve, the slope is

Note: the derivative of an implicit relation usually involves both the x and y coordinates.

Second Derivatives

This idea can be repeated to find second and higher derivatives.

Example 1 continued: In the first example with we differentiate using the quotient rule:

The second derivative is a function, not just of x and y, but also of . We can replace it with the first derivative and simplify.

(This might be a good time to do a quick review of simplifying complex fractions; they occur often in implicit differentiation problems.)

To find the value of the second derivative at a given point we can substitute into either of the two expressions above. At (3, –4) where the derivative has been previously found to be ¾ we have

Or we can use the second form

Example 2 continued: The second example was taken from an AB Calculus exam (2004 AB 4). The first part gave the first derivative and asked students to show that it was correct. This was done (instead of just asking the students to find the first derivative) so that students would be sure to have the correct derivative to use later in the question.

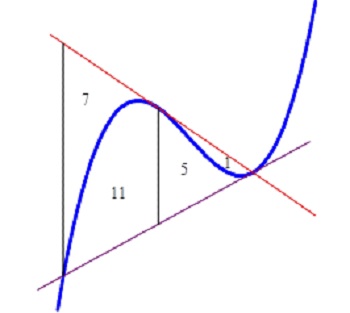

The second part asked students to show that the tangent line is horizontal at the point where x = 3. This included finding the coordinates of the point, (3, 2) and showing that it is on the curve.

The third part of the question asked students to determine whether the point from part (b) was a relative maximum, a relative minimum or neither, and to justify their answer. Since there is no way to determine how the sign of the first derivative changes at the point the First Derivative Test cannot be used. Likewise, the Candidates’ Test (a/k/a the closed interval test) cannot be used without solving for y, and determining the domain of each part. That leaves the Second Derivative Test as the easiest choice.

at (3,2)

Substituting the values into this without doing the algebra to remove the first derivative gives

So, the point (3, 2) is a relative maximum.

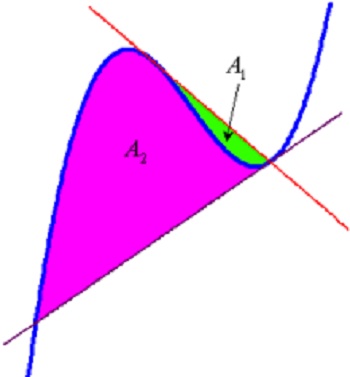

The graph of the relation, an ellipse is shown below.

* Incidentally, there is another clever way of doing example 1: The radius to any point on a circle centered at the origin has a slope of y/x. Since tangents to circles are perpendicular to the radii drawn to the point of tangency, the slope of the tangent must be –x/y.