Accumulation 5: Lines

If you have a function y(x), that has a constant derivative, m, and contains the point then, using the accumulation idea I’ve been discussing in my last few posts, its equation is

This is why I need your help!

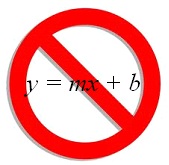

I want to ban all use of the slope-intercept form, y = mx + b, as a method for writing the equation of a line!

The reason is that using the point-slope form to write the equation of a line is much more efficient and quicker. Given a point and the slope, m, it is much easier to substitute into

at which point you are done; you have an equation of the line.

Algebra 1 books, for some reason that is beyond my understanding, insist using the slope-intercept method. You begin by substituting the slope into and then substituting the coordinates of the point into the resulting equation, and then solving for b, and then writing the equation all over again, this time with only m and b substituted. It’s an algorithm. Okay, it’s short and easy enough to do, but why bother when you can have the equation in one step?

Where else do you learn the special case (slope-intercept) before, long before, you learn the general case (point-slope)?

Even if you are given the slope and y-intercept, you can write .

If for some reason you need the equation in slope-intercept form, you can always “simplify” the point-slope form.

But don’t you need slope-intercept to graph? No, you don’t. Given the point-slope form you can easily identify a point on the line,, start there and use the slope to move to another point. That is the same thing you do using the slope-intercept form except you don’t have to keep reminding your kids that the y-intercept, b, is really the point (0, b) and that’s where you start. Then there is the little problem of what do you do if zero is not in the domain of your problem.

Help me. Please talk to your colleagues who teach pre-algebra, Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2 and pre-calculus. Help them get the kids off on the right foot.

Whenever I mention this to AP Calculus teachers they all agree with me. Whenever you grade the AP Calculus exams you see kids starting with y = mx + b and making algebra mistakes finding b.