In my last post we discussed the five shapes of a graph. Hopefully, that activity, which is posted under the Resources tab above, helped your students discover that

- A function is increasing and concave up, on any interval where its first derivative is positive and its second derivative is positive, like y = sin(x) on

.

- A function is increasing and concave down, on any interval were its first derivative is positive and its second derivative is negative, like y = sin(x) on

.

- A function is decreasing and concave up, on any interval where its first derivative is negative and its second derivative is positive, like y = sin(x) on

.

- A function is decreasing and concave down, on any interval where its first derivative is negative and its second derivative is negative, like y = sin(x) on

.

- To which we will add a function is linear where its first derivative is constant and its second derivative is zero.

Separating the increasing/decreasing behavior from the concavity:

- On an interval where the first derivative is positive the graph is increasing, and on an interval where the first derivative is negative the function is decreasing.

- On an interval where the second derivative is positive the function is concave, on an interval where the second derivative is negative the graph is concave down.

Be careful when presenting the ideas above.

None of them consider what happens if one of the other of the derivatives is zero or undefined. There is an important theorem which says, and we must be careful here, “If for all x in an interval, , then the function is increasing on that interval.”

True enough, but what about y = x3 on an interval containing the origin? Well, the theorem does not apply, since the derivative is not positive everywhere on the interval. The theorem says nothing about what happens when the derivative is zero, only what happens when it is positive. In such cases we need to return to the definition of increasing (which incidentally does not mention derivatives), to determine that y = x3 is increasing on any interval containing the origin (any interval, anywhere, in fact).

Another thing to be careful of is this: Functions increase or decrease on intervals, not at points. If you are asked if a function is increasing or decreasing at a point, or “Is the velocity increasing when t = ….” interpret the question as asking, “Is there a small open interval containing the point, on which the function is increasing or decreasing.”

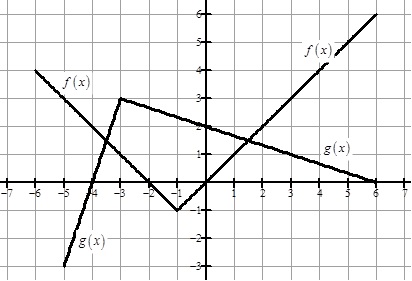

Using the derivative to give this kind of information about the graph is a big part of the calculus and one of the important uses of derivatives. We can determine information by working with the equation of the derivative. We can also work from the graph of the derivative. This is often easier since it is easy to tell from the graph when the derivative is positive or negative. From the graph of the derivative, we can also see where the derivative is increasing or decreasing, and this tells us the sign of the second derivative and hence about the concavity of the function. I will discuss this in a later post.

Next: Joining the Pieces