You’re now ready to learn about the derivative – one of the two big tools of calculus.

If you graph a function on your calculator and Zoom-In several times at a point on it graph, your graph will eventually look like a straight line. Try it now; pick your favorite function and Zoom in where it looks most curvey. Very close up most functions look like lines. (There are exceptions.) The “slope” of this “line” is the derivative.

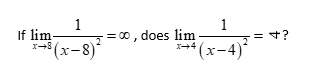

A little more precisely, the derivative is the slope of the line tangent to the graph at the point you compute it. It is found by considering a line that intersects the graph at two points and then moving the second point to the first using a limiting process. So, derivatives are always limits.

The derivative is derived from the function itself. (That’s where the name comes from.)

The difference between the slope of a line and the slope of the curve is this: lines have a constant slope; curves have slopes that change as you move along the graph.

Since the derivative changes as you move along the graph, “derivative” also means the function that gives the derivative (slope) at each point. You will learn how to derive this function from the equation of the curve.

You will often need to write the equations of this tangent line. No, biggie: you have the point and the slope. That’s all you need.

(Hint: Forget slope-intercept! When writing the equation of a line is easiest way is to use the point-slope form, where the point is

and the slope is the derivative denoted by

. You only need these three numbers – the two coordinates of a point and the derivative at that point). Drop them into the point-slope equation and you’re done.)

The tangent line is not your geometry teacher’s tangent line. Curves are not circles, so the tangent line may cross the curve at another point, or several other points. Sometimes the tangent line will even cross the curve at the point at the point of tangency!

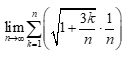

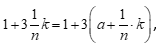

You will begin by learning how to find the derivative using limits (all derivatives are limits). Then you will learn how to find the derivatives by bypassing the limiting process. That’s a good-news-bad-news thing. The good news is the formulas for finding derivatives make your work very easy and straightforward. The bad news is you’ll have to memorize the formulas. Sorry! Just giving you a heads-up.

Units: Like the slope of a line, the derivative is the instantaneous rate of change of the function at the point you calculate it. Since it is a rate of change, it has rate-of-change units: miles per hour, meters per second, furlongs per fortnight, figs per Newton.

Units are important:

Using the derivative, you will be able to find out useful things about a function. You can find exactly where the function is increasing and decreasing, exactly where it has its extreme values (its maximum and minimum), where it has “problems,” and other things. These in turn lead to practical considerations for the solution of problems in engineering, science, economics, finance, and any field that uses numbers.

Summary: Derivative has several meanings:

- The slope of the tangent line to the curve, a/k/a “the slope of the curve.”

- The function that gives the slope at any point.

- The instantaneous rate of change of the of the dependent variable (y) with respect to the independent variable (x). Therefore, its units are the units of y divided by the units of x.

Derivatives are important and useful. So, let’s drive ahead.

Course and Exam Description Unit 2 topics 2.1 to 2.4