Jean Gaston Darboux

1842 – 1917

Jean Gaston Darboux was a French mathematician who lived from 1842 to 1917. Of his several important theorems the one we will consider says that the derivative of a function has the Intermediate Value Theorem property – that is, the derivative takes on all the values between the values of the derivative at the endpoints of the interval under consideration.

Darboux’s Theorem is easy to understand and prove but is not usually included in a first-year calculus course (and is not included on the AP exams). Its use is in the more detailed study of functions in a real analysis course.

You may want to use this as an enrichment topic in your calculus course, or a topic for a little deeper investigation. The ideas here are certainly within the range of what first-year calculus students should be able to follow. They relate closely to the Mean Value Theorem (MVT). I will suggest some ideas (in blue) to consider along the way.

More precisely Darboux’s theorem says that

If f is differentiable on the closed interval [a, b] and r is any number between f ’ (a) and f ’ (b), then there exists a number c in the open interval (a, b) such that f ‘ (c) = r.

Differentiable on a closed interval?

Most theorems in beginning calculus require only that the function be differentiable on an open interval. Here, obviously, we need a closed interval so that there will be values of the derivative for r to be between.

The limit definition of derivative requires a regular two-sided limit to exist; at the endpoint of an interval there is only one side. For most theorems this is enough. Here the definition of derivative must be extended to allow one-sided limits as x approaches the endpoint values from inside the interval. Also note that if a function is differentiable on (a, b), then it is differentiable on any closed sub-interval of (a, b) that does not include a or b.

Geometric proof [1]

Consider the diagram below, which shows a function in blue. At each endpoint draw a line with the slope of r. Notice that these two lines have a slope less than that of the function at the left end and greater than the slope at the right end. At least one of these lines must intersect the function at an interior point of the interval. Before reading on, see if you and your students can complete the proof from here. (Hint: What theorem does the top half of the figure remind you of?)

On the interval between the intersection point and the end point we can apply the Mean Value Theorem and determine the value of c where the tangent line will be parallel to the line through the endpoint. At this point f ‘(c) = r. Q.E.D.

On the interval between the intersection point and the end point we can apply the Mean Value Theorem and determine the value of c where the tangent line will be parallel to the line through the endpoint. At this point f ‘(c) = r. Q.E.D.

Analytic Proof [2]

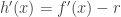

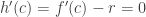

Consider the function  . Since f(x) is differentiable, it is continuous;

. Since f(x) is differentiable, it is continuous;  is also continuous and differentiable. Therefore, h(x) is continuous and differentiable on [a, b]. By the Extreme Value Theorem, there must be a point, x = c, in the open interval (a, b) where h(x) has an extreme value. At this point h’ (c) = 0.

is also continuous and differentiable. Therefore, h(x) is continuous and differentiable on [a, b]. By the Extreme Value Theorem, there must be a point, x = c, in the open interval (a, b) where h(x) has an extreme value. At this point h’ (c) = 0.

Before reading on see if you can complete the proof from here.

Q.E.D.

Exercise: Compare and contrast the two proofs.

- In the geometric proof, what does

represent? Where does it show up in the diagram?

represent? Where does it show up in the diagram?

- How do both proofs relate to the Mean Value Theorem (or Rolle’s Theorem).

The function  represents the vertical distance from f(x) to

represents the vertical distance from f(x) to  . In the diagram, this is a vertical segment connecting f(x) to

. In the diagram, this is a vertical segment connecting f(x) to  .This expression may be positive, negative, or zero. In the diagram, at the point(s) where the line through the right endpoint intersects the curve and at the endpoint h(x) = 0. Therefore, h(x) meets the hypotheses of Rolle’s Theorem (and the MVT), and the result follows.

.This expression may be positive, negative, or zero. In the diagram, at the point(s) where the line through the right endpoint intersects the curve and at the endpoint h(x) = 0. Therefore, h(x) meets the hypotheses of Rolle’s Theorem (and the MVT), and the result follows.

The line through the right endpoint will have equation the  This makes

This makes  . When differentiated and the result will be

. When differentiated and the result will be  the same expression as in the analytic proof.

the same expression as in the analytic proof.

Also, you may move this line upwards parallel to its original position and eventually it will be tangent to the graph of the function. (See my posts on MVT 1 and especially MVT 2).

Exercise:

Consider the function f(x) = sin(x)

- On the interval [1,3] what values of the derivative of f are guaranteed by Darboux’s Theorem? .

- Does Darboux’s theorem guarantee any value on the interval

![[0,2\pi ]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C2%5Cpi+%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) ? Why or why not?

? Why or why not?

Answers:

- f ‘(x) = cos(x). f ‘ (1) = 0.54030 and f ‘ (3) = -0.98999. So the guaranteed values are from -0.98999 to 0.54030.

- No. f ‘ (x) = 1 at both endpoints, so there are no values between one and one.

Another interesting aspect of Darboux’s Theorem is that there is no requirement that the derivative f ‘(x) be continuous!

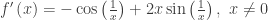

A common example of such a function is

With  .

.

This function (which has appeared on the AP exams) is differentiable (and therefore continuous).There is an oscillating discontinuity at the origin. The derivative is not continuous at the origin. Yet, every interval containing the origin as an interior point meets the conditions of Darboux’s Theorem, so the derivative while not continuous has the intermediate value property.

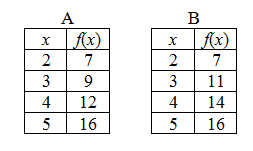

AP exam question 1999 AB3/BC3 part c:

Finally, what inspired this post was a recent discussion on the AP Calculus Community bulletin board about the AP exam question 1999 AB3/BC3 part c. This question gave a table of values for the rate, R, at which water was flowing out of a pipe as a differentiable function of time t. The question asked if there was a time when R’ (t) = 0. It was expected that students would use Rolle’s Theorem or the MVT. There was a discussion about using Darboux’s theorem or saying something like the derivative increased (or was positive), then decreased (was negative) so somewhere the derivative must be zero (implying that derivative had the intermediate value property). Luckily, no one tried this approach, so it was a moot point.

Take a look at the problem with your students and see if you can use Darboux’s theorem. Be sure the hypotheses are met.

Answer (try it yourself before reading on):

The function is not differentiable at the endpoints. But consider an interval like [0,3]. Using the given values in the table, by the MVT there is a time t = c where R‘(c) = 0.8/3 > 0, and there is a time t = d on the interval [21, 24] where R‘(d) = -0.6/3 < 0. The function is differentiable on the closed interval [c, d] so by Darboux’s Theorem there must exist a time when R’(t) = 0. Admittedly, this is a bit of overkill.

References:

- After Nitecki, Zbigniew H. Calculus Deconstructed A Second Course in First-Year Calculus, ©2009, The Mathematical Association of America, ISBN 978-0-883835-756-4, p. 221-222.

- After Dunham, William The Calculus Gallery Masterpieces from Newton to Lebesque, © 2005, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-09565-3, p. 156.

Both these book are good reference books.

Updated: August 20, 2014, and October 4, 2017