Good Question 2, continued.

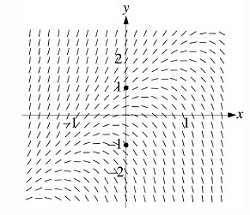

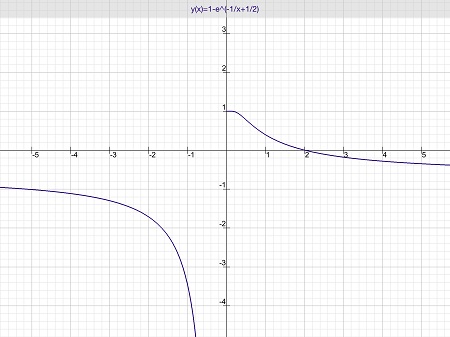

Today we continue looking at Good Question 2 from our last post. The jumping off place was the BC calculus exam question 5 from 2002. We looked at the differential equation and its slope field and discussed the questions asked on the exam. Then we saw how to actually solve the equation and found the general solution to be

.

The general solution of a differential equation contains a constant and therefore defines a family of functions all of whom satisfy the differential equation; they have similar, but slightly different graphs. Let’s look at and discuss the similarities and differences.

In using this with a class I suggest you present it step by step with lots of questions (more than I have here) to help them find the way to the full description of the family of functions. Alternatively, you could be very general and ask them to discuss (and justify) end behavior and the location of any extreme values or other interesting features individually or in small groups.

The Rule of Four says that all mathematical situations should be looked at analytically (i.e. with equations), graphically, numerically and verbally. In the previous post the analytic considerations were foremost and the slope field accounted for the graphical aspect. Euler’s method was numerical. Today the numerical comes to the forefront to help us discuss the graph. (Fro the verbal, well, I’ve never been accused of not being verbose, writing-wise.)

The two numbers that need to be considered are the parameter C and numerical size of e2x.

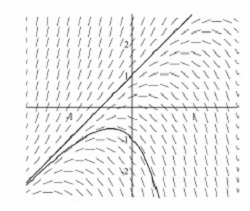

When C = 0 the solution reduces to y = 2x + 1. This is a line. If we rewrite the general solution as and realize that e2x is always positive, we can see that solutions with C > 0 lie above the line and those with C < 0 lie below.

Left end behavior

Look at the x-values moving from the origin to the left; where x is negative and getting larger in absolute value. Here e2x will get very small and the solution will all get closer to the line y = 2x + 1. If C > 0 the solutions will be a little above the line and if C < 0 they will lie just below the line.

Therefore, the left end behavior is that the functions approach y = 2x + 1 as a slant asymptote.

Maximum Points

In the previous post we determined that the origin was a maximum point of the solution that contained the origin (C = –1). Are there extreme points for any other solutions?

The maximums occur where , that is where

or

. We know they are maximums by the second derivative test:

when C < 0. All the curves with C < 0 are concave down on their entire domain.

What does this mean? It means that for all the members of the family of solutions that have C < 0 have a maximum point, and that maximum point will be on the line .

Which members of the family can have maximums? Since lies below

only those with C < 0 will have maximums.

The graph above shows 30 members of the family with C = –3 (bottom curve) to C = –0.1 (top curve). The equation of the black line is y= 2x and the equation of the blue line is y= 2x + 1. Note that all the maximum points lie on the line y= 2x.

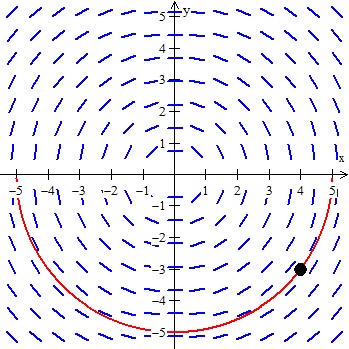

The curves with C > 0 lie above the line y= 2x + 1. For these curves

This expression will be positive when or

. In other words, when the curve lies above the line y= 2x + 1, exactly those with C > 0.

Therefore, all of these members of the family are concave up everywhere and since there is nowhere where their derivative is zero, there are no minimum points. See the graph below

Right end behavior

From what we have determined above for C > 0 , and for C < 0,

.

When graphing calculators were first required on the AP calculus exams (1995) there were, for a few years, questions asking students to analyze some aspect of a family of functions. See for example 1995 BC 5, 1996 AB4/BC4, 1997 AB 4, 1997 BC 4, 1998 AB2/BC2. They seem to have stopped asking such questions. Too bad; there is some interesting calculus to be had in family of function questions.