The answers to the True-False quiz at the end of the last post are all false. This brings us to absolute value, another topic I want to concentrate on for my upcoming Algebra 1 class. Absolute value becomes a concern in calculus too which I will discuss as the last example below.

There a several “definitions” of absolute value that I’ve seen over the years which I mostly do not like

- The number without a sign – awful: all numbers except zero have a sign

- The distance from zero on the number line – true, but not too useful especially with variables

- The larger of a number and its opposite – true, but not to useful with variables

So I propose to give them an algorithm: If the number is positive, then the absolute value is the same number; if the number is negative, then its absolute value is its opposite. Of course, this is really the definition.

So I’ll soon express this in symbols

Now interestingly this is probably the first piecewise defined function an Algebra 1 student may see, or at least the first one that’s not artificial. So this is a good place to start talking about piecewise defined function and the importance of talking about the domain. And of course, we’ll have to take a look at the graph.

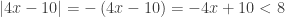

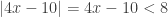

Sometimes we will have to start solving equations and inequalities with absolute values. So here is the next thing I understand but do not like and will try to avoid. Solve the equation:  , Answer including work:

, Answer including work:  . But I think a longer way around is also better:

. But I think a longer way around is also better:

If  then

then  so

so  or if

or if  , then

, then  Solution:

Solution:  or

or  .

.

Longer? Sure. I hope that by making the students write that a few times that when they get to solving  that it will be natural to say

that it will be natural to say

If  then

then  so

so  or if

or if  , then

, then  Solution:

Solution:  or

or

The last case may take a little more discussion. Solve  . Starting the same way

. Starting the same way

If  then

then  so

so  which really means

which really means

if  , then

, then  which really means

which really means  . Then the union of these two sets looks like an intersection. The solution is

. Then the union of these two sets looks like an intersection. The solution is

Quite often the equation and the two types of inequalities are treated as separate problems: with = you go with  on the other side, with > you have a union pointing away from the origin and with < you have somehow an intersection. Who needs to remember all that when this idea works all the time?

on the other side, with > you have a union pointing away from the origin and with < you have somehow an intersection. Who needs to remember all that when this idea works all the time?

Example: Solve

If  , then

, then  and

and  , so

, so  and

and  or more precisely

or more precisely  latex 4x-10\ge 0$, then

latex 4x-10\ge 0$, then  and

and  , so

, so  and

and  or more precisely

or more precisely  . The union again becomes an intersection and the answer is

. The union again becomes an intersection and the answer is

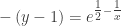

Finally an example from calculus. On the 2008 AB exam, question 5 asked student to find the particular solution of a differential equation with the initial condition  . After separating the variables, integrating, including the “+C” and substituting the initial condition students arrived at this equation which they now need to solve for y:

. After separating the variables, integrating, including the “+C” and substituting the initial condition students arrived at this equation which they now need to solve for y:

How can you lose the absolute value sign? Simple, near the initial condition where y = 0,  so replace

so replace  with

with  and then go ahead and solve for y

and then go ahead and solve for y

I don’t think I’ll try this one in Algebra 1, but maybe it will come in handy when they get to calculus.

so

. Continue and solve for y.