The eighth in the Graphing Calculator / Technology series

Here are some hints for graphing Taylor polynomials using technology. (The illustrations are made using a TI-8x calculator. The ideas are the same on other graphing calculators; the syntax may be slightly different.)

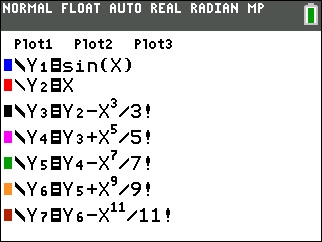

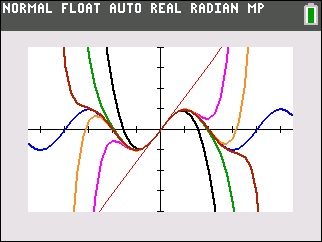

Each successive term of a Taylor polynomial consists of all the previous terms plus one new term. To show students how Taylor polynomials closely approximate a function (in the interval of convergence, of course), enter the function as Y1. Then enter the first term of the polynomial as Y2. Enter the next polynomial as Y3 = Y2 + the second term; enter the next as y4 = Y3 + the next term, and so on.

The example is the McLaurin series for sin(x) centered at the origin:

Each will graph one at a time. Watching them graph, one at a time, is instructive as well; each curve approximates the sine curve (in black) further and further away from the origin.

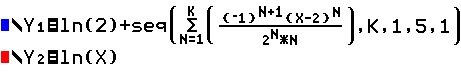

Another way to graph the polynomials is to enter them as a sequence of sums. The example this time is ln(x) centered at x = 2:

The syntax is seq( series in sigma notation, indexing variable, start value, end value [,step]). Notice from the figure that the indexing variable, K, is above the sigma.

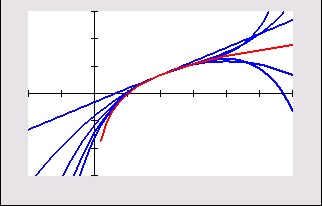

The individual polynomials graph in the same color (blue); the function is shown in red.

Comparing the two graphs (sin(x) and ln(x)) is a good way to start a discussion about the interval of convergence – ask what is different about the graphs as more polynomials are graphed on each. Notice that unlike the sin(x) series the ln(x) polynomials only come close to the function in a limited interval (0, 4) centered at x = 2.

Comparing the two graphs (sin(x) and ln(x)) is a good way to start a discussion about the interval of convergence – ask what is different about the graphs as more polynomials are graphed on each. Notice that unlike the sin(x) series the ln(x) polynomials only come close to the function in a limited interval (0, 4) centered at x = 2.

Desmos is also a good program to use to illustrate Taylor and McLaurin polynomials (as are Geogebra and Winplot). The use of the sliders makes it possible to see the successive polynomials quickly. They also help students see the interval of convergence as higher degree polynomials hug the graph on wider intervals (sin(x)), or stay within the same interval (ln(x)). The Desmos illustration with slider for the sin(x) centered at the origin is here and for ln(x) centered at x = 2 is here. Study the input on the left side and enter Taylor polynomials for other functions.

The fifth degree Taylor polynomial for sin(x) centered at the origin.The interval of convergence is all real numbers. Each polynomial “hugs” the graph on wider intervals.

The fifth degree Taylor polynomial for ln(x) centered at x = 2. The interval of convergence is 0 < x < 4. The polynomials all leave the graph outside of this interval.

Coming soon

Feb 14th, Geometric Series – Far Out