Recently, a reader wrote and suggested my post on continuity would be improved if I discussed one-sided continuity. This, along with one-sided differentiability, is today’s topic.

The definition of continuity requires that for a function to be continuous at a value x = a in its domain  and that both values are finite. That is, the limit as you approach the point in question be equal to the value at that point. This limit is a two-sided limit meaning that the limit is the same as x approaches a from both sides. That definition is extended to open intervals, by requiring that for a function to be continuous on an open interval, that it is continuous at every point of the interval

and that both values are finite. That is, the limit as you approach the point in question be equal to the value at that point. This limit is a two-sided limit meaning that the limit is the same as x approaches a from both sides. That definition is extended to open intervals, by requiring that for a function to be continuous on an open interval, that it is continuous at every point of the interval

How do you check every point? One way is to prove the limit in the definition in general for any point in the open interval. Another is to develop a list of theorems that allow you to do this. For example, f(x) = x can be shown to be continuous at every number. Then sums, differences, and products, of this function allows you to extend the property to polynomials and then other functions.

But what about a function that has a domain that is not the entire number line? Something like  . Here,

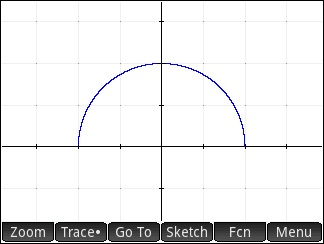

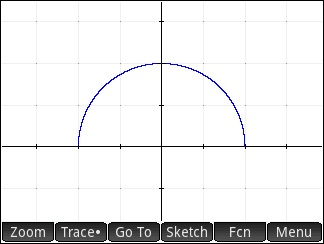

. Here,  ; the function is defined at the endpoints. A look at the graph shows a semi-circle that appears to contain the endpoints (–2, 0) and (2, 0). The function is continuous on the open interval (–2, 2) but cannot be continuous under the regular definition since the limit at the endpoints does not exist. The limit does not exist because the limit from the left at the left-endpoint, and the limit from the right at the right endpoint do not exist. What to do?

; the function is defined at the endpoints. A look at the graph shows a semi-circle that appears to contain the endpoints (–2, 0) and (2, 0). The function is continuous on the open interval (–2, 2) but cannot be continuous under the regular definition since the limit at the endpoints does not exist. The limit does not exist because the limit from the left at the left-endpoint, and the limit from the right at the right endpoint do not exist. What to do?

What is done is to require only that the one-sides limits from inside the domain exist. Here they do: and the

and the  and since the limits equal the values we say the function is continuous on the closed interval [–2, 2]. In general, when you say a function is continuous on a closed interval, you mean that the one-sided limits from inside the interval exist and equal the endpoint values.

and since the limits equal the values we say the function is continuous on the closed interval [–2, 2]. In general, when you say a function is continuous on a closed interval, you mean that the one-sided limits from inside the interval exist and equal the endpoint values.

You can determine that the limits exist by finding them as in the example above. Another way is to realize that if a < b < c < d and the function is continuous on the open (or closed) (a, d) then it is continuous on the closed interval [b c].

Why bother?

The reason we take this trouble is because for some reason the proof of the theorem under consideration requires that the endpoint value not only exist but hooks up with the function to make it continuous. Thus, the continuity on a closed interval is included in the hypotheses of theorem where this property is required. For example, the Intermediate Value Theorem would not work on a function that had no endpoints for  to be between. Also, the Mean Value Theorem requires you to find the slope between the endpoints, so the endpoint needs to be not only defined, but attached to the rest of the function.

to be between. Also, the Mean Value Theorem requires you to find the slope between the endpoints, so the endpoint needs to be not only defined, but attached to the rest of the function.

One-sided differentiability

The definition of the derivative at a point also requires a two-sided limit to exist at the point. Most of the early theorems in calculus require only that the function be differentiable on an open interval.

Is it possible to define differentiability at the endpoint of an interval? Yes. It’s done in the same way by using a one-sided limit. If x = a is the left endpoint of an interval, then the derivative from the right at that point is defined as

.

.

By letting h approach 0 only from the right, you never consider values outside the interval. (At the right endpoint a similar definition is used with  ).

).

So why don’t we ever see one-sided derivatives? Because the theorems do not need them to prove their result. Hypotheses of theorems should be the minimum requirements needed, so if there is no need for the function to be differentiable at an endpoint, this is not listed in the hypotheses. This makes the hypothesis less restrictive and, therefore, covers more situations.

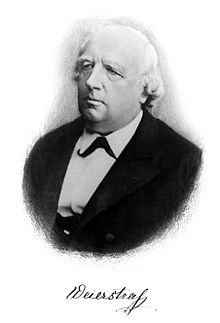

One theorem, beyond what is usually covered in beginning calculus, where endpoint differentiability is needed is Darboux’s Theorem. Darboux’s Theorem is sometime called the Intermediate Value Theorem for derivatives. It says that the derivative takes on all values between the derivatives at the endpoints, and thus needs the one-sided derivatives at the endpoints to exist. Interestingly, Darboux’s Theorem does not require the function to be continuous on the open interval between the endpoints.

.

definition of continuity. In that definition was the definition of limit. So, which came first – continuity or limit? The ideas and situations that required continuity could only be formalized with the concept of limit. So, looking at functions that are and are not continuous helps us understand what limits are and why we need them.

definition of continuity. In that definition was the definition of limit. So, which came first – continuity or limit? The ideas and situations that required continuity could only be formalized with the concept of limit. So, looking at functions that are and are not continuous helps us understand what limits are and why we need them.