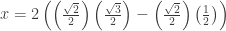

A friend of mine e-mailed me yesterday with a question: Her class was using the Law of Cosines and came up with a solution of  , but the “correct” answer was

, but the “correct” answer was  . She wanted to know, having gotten the first answer, how do you get to the second from it. The answers are equivalent:

. She wanted to know, having gotten the first answer, how do you get to the second from it. The answers are equivalent:  I figured it out this way

I figured it out this way

But in fact, I had worked that from the second back to the first. So I sent the problem to another friend who sent this back:  This is a more formal way of what I did. (The solution k = 6 gives the same expression.) But the real question is how is a student supposed to know any of this? My friend wrote, “This problem seems really complicated for multiple=choice. Remember that this is what we had to do AFTER we had done law of cosines to get to that first step.” I agree. Then I asked her for the original problem, which is what I should have done in the first place. The original problem was to find the base of an isosceles triangle with a vertex angle of 30o and congruent sides of 2. Well that’s a whole different story:

This is a more formal way of what I did. (The solution k = 6 gives the same expression.) But the real question is how is a student supposed to know any of this? My friend wrote, “This problem seems really complicated for multiple=choice. Remember that this is what we had to do AFTER we had done law of cosines to get to that first step.” I agree. Then I asked her for the original problem, which is what I should have done in the first place. The original problem was to find the base of an isosceles triangle with a vertex angle of 30o and congruent sides of 2. Well that’s a whole different story:

And also

And also  works the same way. But there is yet another way: we could draw a different perpendicular and get a 30-60-90 triangle (not to scale):

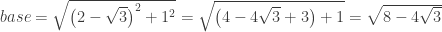

works the same way. But there is yet another way: we could draw a different perpendicular and get a 30-60-90 triangle (not to scale):  Then using the Pythagorean Theorem on the lower triangle:

Then using the Pythagorean Theorem on the lower triangle:

The morals of the story:

- First as we have all discovered, when a student asks, “What do I do now?” or “How can I get from here to here?” Go back to the original question. Do not jump in the middle and answer the wrong question.

- Second, while I am definitely not against multiple-choice problems, this is a horrible multiple-choice question. It is horrible because there are so many good ways to do it, but they lead to different looking answers. Students should not be penalized for doing good mathematics. It is fine to require a student to do a problem by a certain method if you are currently teaching that method. But with no method specified, the students should not get a correct answer and then have to really struggle to get your answer. On the other hand, this is a very good questions, precisely because there are so many ways to do it and because the answers look different.