Today, for some summer fun, let’s look at synthetic division a/k/a synthetic substitution. I’ll assume you all know how to do that since it is a pretty common pre-calculus topic and even comes up again in calculus.

Today, for some summer fun, let’s look at synthetic division a/k/a synthetic substitution. I’ll assume you all know how to do that since it is a pretty common pre-calculus topic and even comes up again in calculus.

Why Does Synthetic Division Work?

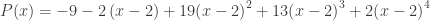

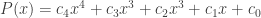

An example: consider the polynomial

.

.

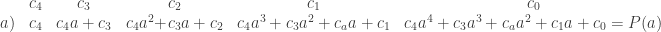

This can be written in nested form like this

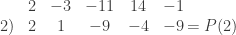

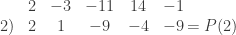

To evaluate this last expression at, say x = 2, we do the arithmetic as follows:

- 2 x 2 – 3 = 1

- 2 x 1 – 11 = –9

- 2 x (–9) + 14 = –4

- 2 x (–4) – 1 = – 9 = f(2)

Notice that this requires only multiplication and addition or subtraction, no raising to powers. More to the point, this is the same arithmetic, in the same order when you do the evaluation by synthetic division, and the work is a little easier to keep track of.

Synthetic division has another advantage: the other numbers in the second row are the coefficients of a quotient polynomial, a polynomial of one less degree that the original. So,

The Remainder Theorem and the Factor Theorem

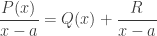

In general, a polynomial of degree n, divided by a linear factor (x – a) gives a polynomial Q(x) of degree n – 1 and a remainder R

Or

From here it is easy to see that  . This is called the remainder theorem. It has a corollary called the factor theorem: If R = 0, then (x – a) is a factor of P(x).

. This is called the remainder theorem. It has a corollary called the factor theorem: If R = 0, then (x – a) is a factor of P(x).

Calculus

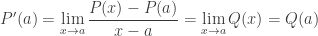

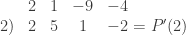

But wait there is more: differentiating the equation above using the product rule gives

and substituting x = a gives

and substituting x = a gives

. The value of the quotient polynomial at a is the derivative of the original polynomial at a.

. The value of the quotient polynomial at a is the derivative of the original polynomial at a.

Of course, we could also rewrite the same equation as  . Then

. Then

Taylor Series

But wait, there’s even more.

A polynomial is a Maclaurin series in which all the terms after the nth term are zero. When you students are first learning how to write a Taylor series, by finding all the derivatives and substituting in the general term, a good exercise is to have them write the Taylor series for a polynomial centered away from the origin. For the example above:

Then ask them to expand the expression above and collect term etc. They should get the original polynomial again (and have some great practice expand powers of a binomial).

Can synthetic division help us? Yes, of course. Here, is the original computation again:

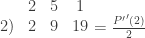

If we ignore the –9 and divide the quotient numbers by 2 we get

And again

One more time

What do you see? Right, the last numbers in each computation, –9, –2, 19, 13, and 2, are the coefficients of the Taylor polynomial!

If you really want to dive this home and have some more summer fun here’s the start of a proof (at least for n = 4). Let

and divide this by a:

and divide this by a:

Again

And I’ll leave the rest to you. Really, why should I have all the fun?

.