Why L’Hospital’s Rule?

We are now at the point where we can look at a special technique for finding some limits. Graph on your calculator y = sin(x) and y = x near the origin. Zoom in a little bit. The line is tangent to sin(x) at the origin and their values are almost the same. Look at the two graphs near the origin and see if you can guess the limit of their ratio at the origin: ?.

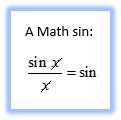

In this example, if you substitute zero into the expression you get zero divided by zero and there is no way to divide out the zero in the dominator as you could with rational expressions.

This kind of thing is called an indeterminate form. The limit of an indeterminate form may have a value, but in its current form you cannot determine what it is. When you studied limits, you were often able to factor and divide out the denominator and find the limit for what was left. With you can’t do that.

But by replacing the expressions with their local linear approximations, the offending factor will divide out leaving you with the ratio of the derivatives (slopes). This limit may be easier to find.

The technique is called L’Hospital’s Rule, after Guillaume de l’Hospital (1661 – 1704) whose idea it wasn’t! He sort of “borrowed’ it from Johann Bernoulli (1667 – 1784).

L’Hospital’s Rule gives you a way of finding limits of indeterminate forms. You will look at indeterminate forms of the types and

. The technique may be expanded to other indeterminate forms like

which are not tested on the AP Calculus exams.

Like other “rules” in math, L’Hospital’s Rule is really a theorem. Before you use it, you must check that the hypotheses are true. And on the AP Calculus exams you must show in writing that you have checked.

Course and Exam Description Unit 4 Topic 7

Hi Lin, et al. –

I tell my students that for any mathematical concept, they should be able to (1) understand it, (2) define it, (3) do it, (4) apply it (not necessarily in that order). The short answer to the title of your post is, l’Hospital’s rule is the “bread-and-butter” technique for “doing” limits. Here’s how I introduce l’Hospital’s rule:

• Plot the graph of f(x) = (x^3 – 8x^2 + 21x – 14)/(ln x)

• Explain why f(1) is undefined.

• What does the limit of f(x) seem to be as x approaches 1?

[from graph, answer is 8.]

• Find limit as x approaches 1 of the fraction

(d/dx(x^3 – 8x^2 + 21x – 14))/(d/dx(ln x))

[Answer is also 8. Remarkable!]

• Look up l’Hospital’s rule in you text, and write a statement of it.

• Use l’Hosptal’s rule for a couple more examples.

[Show the students an acceptable format.]

The advantage of this approach over “derive it then use it” is students first see what it is and how to use it. So when they do derive it, they have an “Aha! That’s why it works!” rather than “Huh? Why are we doing this?”

All the best to you and your students.

Paul

LikeLike

Paul – Thanks again for your contribution

LikeLike